By Josh Freeman, M.D.

Medicine and Social Justice, Nov. 2, 2012

Sometimes the starkest realities are hidden by the language that we choose to speak about them. This week I attended two important conferences, the annual American Public Health Association (APHA) meeting of about 8,000 or more public health workers from across the country, and, on the day preceding it, the annual Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP) meeting, with about 400 doctors and medical students.

While the PNHP program was more targeted, examining the impact of lack of access to health care in the U.S. on the health of our people, it also included international participants. One, Dr. Alex Benos of Greece, talked articulately about the impact of European Union and IMF imposed “austerity” measures on the health of the Greek people — so bad that the child poverty rate there has risen to 16 percent. The impact of the penalties for “bad” (albeit sanctioned and even encouraged by governments) behavior by bankers is being borne by the people, and especially the poorest, in Greece, in Spain, in Portugal – and in the U.S., where the child poverty rate, 23 percent, still significantly exceeds that of Greece. While they have been dramatically underplayed by the U.S. media, there have been massive, massive, and regular demonstrations against these attacks on the people, and in Greece (as elsewhere) physicians such as Dr. Benos are there on the lines with their patients, providing medical care and demanding the core basic social services that their patients need.

“Health and health care,” Dr. Benos says, “are not commodities that exist to drive the economy. They are among the social goals which we have an economy to achieve.”

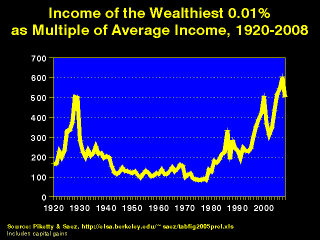

Think about that. We have been so inundated with news articles, pundits, politicians, and others talking about The Market, about the need for austerity, that we have forgotten to ask the key question of “Why is there an economy? What is the goal of production?” It is the national and international version of the phrase we hear so often in businesses, including hospitals: “No margin, no mission.” Perhaps, but much more important is to have a mission; otherwise it is “No mission, no mission.” When a hospital makes money on its profitable “product lines,” what is the mission? To help provide for the basic health care needs of the poor and uninsured? Or to invest in expanding those already-profitable product lines? If our national and international economies generate wealth, is the goal to provide the basic health needs of those whose labor created that wealth? It is clear what we have, de facto, chosen in the U.S.: since 1992 the top 400 taxpayers have had a 500 percent increase in income, and the rest of the top 5 percent a 150 percent increase. Fifty percent of the total increase in income over that period has gone to the top 400 people, and 93 percent to the top 5 percent!

”Solidarity,” Dr. Benos adds, “means no one should be left alone in this crisis.”

His work and that of other Greek physicians is to be sure that this definition of solidarity is the one they live by. For us, in the U.S., a stronger sense of social solidarity would be important; indeed, any sense of social solidarity would be an improvement. The evil myth propagated by many in the U.S. is that when we support the core needs of the most vulnerable, we weaken the economy; in fact, the reverse is true. Providing a core set of social service, including health care, education, housing, food, and opportunity, increases our ability to be a strong society. It is the opposite, the concentration of all wealth in a few, that jeopardizes our future. Trickle down, it should be clear now, doesn’t happen.

“The ideology,” said Dr. Andrew Coates, another speaker and PNHP president-elect, “is that whatever is private is good and whatever is public is bad. It is not true, and it is certainly not cheaper.” Let us compare the U.S. to our closest neighbor, Canada, where most health care services are privately delivered, but are paid for by a single payer, the government. The U.S. spends $8,230 per capita on health care, of which $5,290 are public dollars (counting not only direct expenditures for Medicare, Medicaid, VA, military, and federal, state and local employees and retirees, but also the foregone tax revenue resulting from employer contributions to health insurance being tax exempt). In Canada, total expenditures are $4,440 per capita. Thus our public fund expenditures per capita exceed Canada’s total expenditure. Hospital billing administrative costs in the U.S. are $570 per capita and total administrative costs are $2,685; in Canada, the numbers are $182 and $809 respectively. The gap in life expectancy between the highest and lowest quintiles of income was 1.5 years in 1972. In 2011 it was nearly 6 years. Life expectancy is lower in the U.S., as are life years adjusted for disability, infant mortality, and virtually every other health indicator. Our money is not buying value; it is accruing wealth to a few.

That language is important was emphasized by presenters at several of the APHA sessions I attended (there are literally hundreds of them over the course of the conference). Sonja Bettez, from the University of New Mexico, observed that talking about health “disparities” tends to minimize the structural violence done to the populations of people who suffer those disparities, and that in Latin America this term is never used; rather the discussion is of inequities, or inequalities. Broad-based differences in health status between populations based on class, race, and other characteristics are not just disparities, they result from deeply seated societal and social problems. Using the language of disparities serves a political purpose, she notes, as it tends to pre-empt social change by emphasizing individual behavior change. She also notes the absence of the term “social justice” from any of the decennial iterations of Healthy People, not to mention the absence of “racism.” How we label things has a great deal to do with how we think about what is necessary to correct them.

In another vein, Donald Light spoke about pharmaceutical companies and marketing, noting the language of “the risk-benefit” ratio (which I have used in this blog) does not make sense because it doesn’t identify risk of what? Accurately, it is a risk-risk ratio, the risk of harm vs the risk of benefit, or “harm-benefit” ratio. This is more stark, and more correct. Dr. Light also discussed what he calls the “inverse benefit law”: that the more widely marketed and used a drug is, the less benefit and more harm results. This makes sense; the lowest harm-benefit ratio accrues from the limited use of a drug for those specific conditions, and in those specific people, in whom it has been shown to have the most benefit; as the use of the drug expands to conditions for which it has been less clearly shown to be beneficial, the risk of harm does not decrease and the harm-benefit ratio increases.

It was a very instructive week, and one in which a lot of information was shared. Sadly, it was not all good, and the future, from the economic crisis in Greece to the health care system in the U.S., is pretty cloudy. But using language carefully and accurately to correctly label problems helps us to identify potential solutions. I think a good touchstone is for us to reject the idea that our health, and that of our families and friends and the entire society, should be a vehicle for profit. Dr. Benos has it right when he says the health is a social good for which we must strive, not a commodity.

Now our task is to make that a reali

ty in the U.S.

http://medicinesocialjustice.blogspot.com/2012/11/let-us-get-language-right-health-is-not.html