By Elisabeth Rosenthal

The New York Times, May 17, 2014

Though the recent release of Medicare’s physician payments cast a spotlight on the millions of dollars paid to some specialists, there is a startling secret behind America’s health care hierarchy: Physicians, the most highly trained members in the industry’s work force, are on average right in the middle of the compensation pack.

That is because the biggest bucks are currently earned not through the delivery of care, but from overseeing the business of medicine.

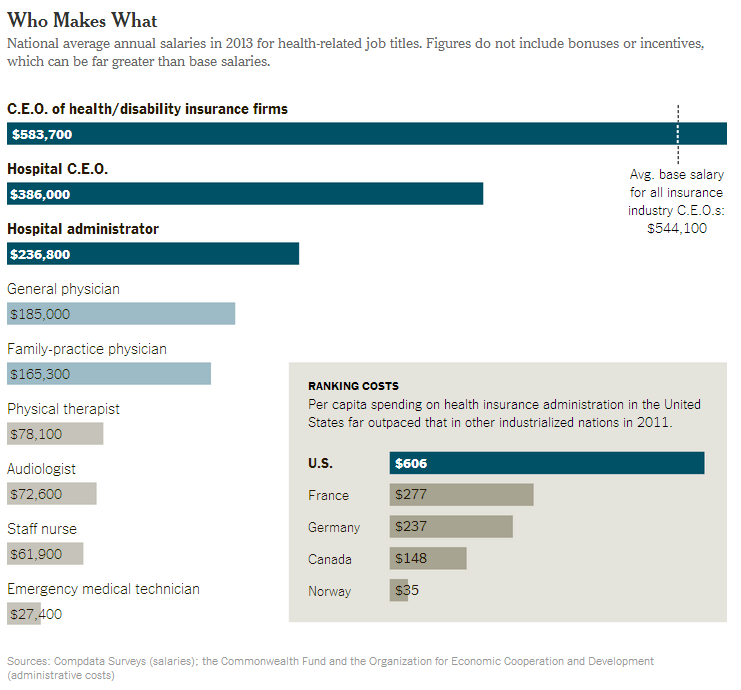

The base pay of insurance executives, hospital executives and even hospital administrators often far outstrips doctors’ salaries, according to an analysis performed for The New York Times by Compdata Surveys: $584,000 on average for an insurance chief executive officer, $386,000 for a hospital C.E.O. and $237,000 for a hospital administrator, compared with $306,000 for a surgeon and $185,000 for a general doctor.

And those numbers almost certainly understate the payment gap, since top executives frequently earn the bulk of their income in nonsalary compensation. In a deal that is not unusual in the industry, Mark T. Bertolini, the chief executive of Aetna, earned a salary of about $977,000 in 2012 but a total compensation package of over $36 million, the bulk of it from stocks vested and options he exercised that year. Likewise, Ronald J. Del Mauro, a former president of Barnabas Health, a midsize health system in New Jersey, earned a salary of just $28,000 in 2012, the year he retired, but total compensation of $21.7 million.

The proliferation of high earners in the medical business and administration ranks adds to the United States’ $2.7 trillion health care bill and stands in stark contrast with other developed countries, where top-ranked hospitals have only skeleton administrative staffs and where health care workers are generally paid less. And many experts say it’s bad value for health care dollars.

“At large hospitals there are senior V.P.s, V.P.s of this, that and the other,” said Cathy Schoen, senior vice president for policy, research and evaluation at the Commonwealth Fund, a New York-based foundation that focuses on health care. “Each one of them is paid more than before, and more than in any other country.”

She added, “The pay for the top five or 10 executives at insurers is pretty astounding — way more than a highly trained surgeon.”

She said that executive salaries in health care “increased hugely in the ‘90s” and that the trend has continued. For example, in addition to Mr. Del Mauro’s $21.7 million package, Barnabas Health listed more than 20 vice presidents who earned over $350,000 on its latest available tax return; the new chief executive earned about $3 million. Data released by Medicare show that Barnabas Health’s hospitals bill more than twice the national average for many procedures. (In 2006, the hospital paid one of the largest Medicare fines ever to settle fraud charges brought by federal prosecutors.)

Hospitals and insurers maintain that large pay packages are necessary to attract top executives who have the expertise needed to cope with the complex structure of American health care, where hospitals and insurers undertake hundreds of negotiations to set prices.

Ellen Greene, a spokeswoman for Barnabas Health, said Mr. Del Mauro’s retirement package was “a function of over four decades of service and reflects his exceptional legacy.” Nearly $14 million was a cumulative payout from a deferred retirement plan, she said, and the remainder included base compensation, a bonus and an incentive plan

Ms. Greene also said Barnabas’s compensation program follows I.R.S. rules and is established by an executive compensation committee with “guidance from a nationally recognized compensation consultant.”

And studies suggest that administrative costs make up 20 to 30 percent of the United States health care bill, far higher than in any other country. American insurers, meanwhile, spent $606 per person on administrative costs, more than twice as much as in any other developed country and more than three times as much as many, according to a study by the Commonwealth Fund.

As a result of the system’s complexity, there are many jobs descriptions for positions that often don’t exist elsewhere: medical coders, claims adjusters, medical device brokers, drug purchasers — not to mention the “navigators” created by the Affordable Care Act.

Among doctors, there is growing frustration over the army of businesspeople around them and the impact of administrative costs, which are reflected in inflated charges for medical services.

“Most doctors want to do well by their patients,” said Dr. Abeel A. Mangi, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the Yale School of Medicine, who is teaming up with a group at the Yale School of Management to better evaluate cost and outcomes in his department. “Other constituents, such as device manufacturers, pharmaceutical companies and even hospital administrators, may not necessarily have that perspective.”

Doctors are beginning to push back: Last month, 75 doctors in northern Wisconsin took out an advertisement in The Wisconsin State Journal demanding widespread health reforms to lower prices, including penalizing hospitals for overbuilding and requiring that 95 percent of insurance premiums be used on medical care. The movement was ignited when a surgeon, Dr. Hans Rechsteiner, discovered that a brief outpatient appendectomy he had performed for a fee of $1,700 generated over $12,000 in hospital bills, including $6,500 for operating room and recovery room charges.

It’s worth noting that the health care industry is staffed by some of the lowest as well as highest paid professionals in any business. The average staff nurse is paid about $61,000 a year, and an emergency medical technician earns just about minimum wage, for a yearly income of $27,000, according to the Compdata analysis. Many medics work two or three jobs to make ends meet.

“It’s stressful, dirty, hard work, and the burnout rate is high,” said Tom McNulty, a 19-year-old college student who volunteers for an ambulance corps outside Rochester. Though he finds it fulfilling, he said he would not make it a career: “Financially, it’s not feasible.”

Elisabeth Rosenthal is a reporter for The New York Times who is writing a series about the cost of health care, “Paying Till It Hurts.” A version of this news analysis appears in print on May 18, 2014, on page SR4 of the New York edition with the headline: Doctor’s Salaries Are Not the Big Cost.