By Michael Hiltzik

Los Angeles Times, September 4, 2019

You’ve got to hand it to Sen. Bernie Sanders for his ability to keep hot-button issues in the forefront of the presidential race.

The latest example is his assertion, made at least twice in the last month, that medical bills drive 500,000 Americans into bankruptcy every year. The Washington Post’s fact-checker column examined the numbers and concluded that Sanders deserved “three Pinocchios” for the statement, which means the Post found it “mostly false” and that Sanders was, basically, lying.

The Post blundered, as the authors of the study on which Sanders based his claim point out. In the real world, Sanders’ assertion that “500,000 Americans will go bankrupt this year from medical bills” is “mostly true.” Medical bankruptcy is an American scandal, and possibly even more common than he or the study’s authors calculate.

It’s also virtually unique to the U.S. among developed countries; when experts from Japan and Europe were asked by the PBS program “Frontline” about the prevalence of medical bankruptcy in their countries, some had trouble even comprehending the question.

What’s clear about the financial consequences of the American system of healthcare financing, which places much of the burden on households, is that they’re widespread and scandalous. One signpost is the rise of crowdfunding campaigns via platforms such as GoFundMe to raise money for families facing medical bills. In a civilized country, public appeals for help with medical bills shouldn’t exist. Yet GoFundMe reports that it hosts more than 250,000 medical campaigns per year, raising more than $650 million a year.

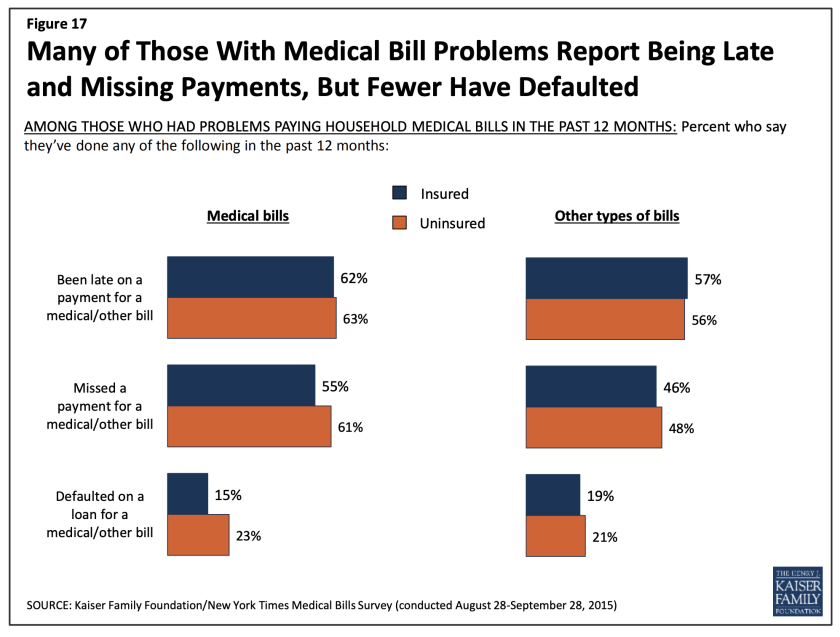

Even households seemingly well-covered by employer health plans can face financial trouble. A survey conducted jointly by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Los Angeles Times found this year that among those consumers, “four in ten report that their family has had either problems paying medical bills or difficulty affording premiums or out-of-pocket medical costs, and about half say someone in their household skipped or postponed some type of medical care or prescription drugs in the past year because of the cost. Seventeen percent say they’ve had to make what they feel are difficult sacrifices in order to pay health care or insurance costs; for some, the sacrifices they report making are extreme.”

Still, pinpointing the number of medical bankruptcies in the United States is difficult, because the causes of bankruptcy typically are multiple. To an extent, the Post’s blunder rests in trying to shoehorn a nuanced phenomenon into its Pinocchio scale, which doesn’t much allow for shades of meaning. So let’s take a look at what the research tells us about the devastation that medical bills can bring to household finances.

First, let’s examine the research underlying Sanders’ figure. It comes from a series of studies dating back to 2005, chiefly by David U. Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler of Harvard and the City University of New York, with the participation at one point or another of Elizabeth Warren, previously a professor at Harvard and currently a U.S. senator and like Sanders a candidate for the Democratic nomination for president.

500,000 Americans will go bankrupt this year from medical bills.

They didn’t go to Las Vegas and blow their money at a casino.

Their crime was that they got sick.

How barbaric is a system that says, “I’m going to destroy your family’s finances because you had cancer”?

— Bernie Sanders (@BernieSanders) August 20, 2019

In their most recent paper, published in March, Himmelstein, Woolhandler and colleagues explained that they mined questionnaires sent to bankrupt debtors by the Consumer Bankruptcy Project and determined that 66.5% of the respondents “very much” or “somewhat” agreed that medical expenses or illness-related work loss contributed to their bankruptcies. That’s “equivalent to about 530 000 medical bankruptcies annually,” they wrote.

The researchers’ earlier papers triggered a scholarly debate that’s still ongoing over how to define “medical bankruptcy.” Is it enough, for example, that medical bills are a contributing factor, since in a typical bankruptcy there are many factors?

Whatever the definition, the numbers proposed by Himmelstein, Woolhandler and Warren have also come under attack. In a 2006 study funded by the health insurance industry, David Dranove and Michael L. Millenson of Northwestern University asserted that “medical bills are a contributing factor in just 17 percent of personal bankruptcies,” mostly affecting households already near poverty.

Dranove and Millenson scoffed at the argument by Himmelstein and Woolhandler that the solution to the problem is a national health insurance program. (Himmelstein and Woolhandler are co-founders of Physicians for a National Health Program, a leading advocate of single-payer universal health coverage.)

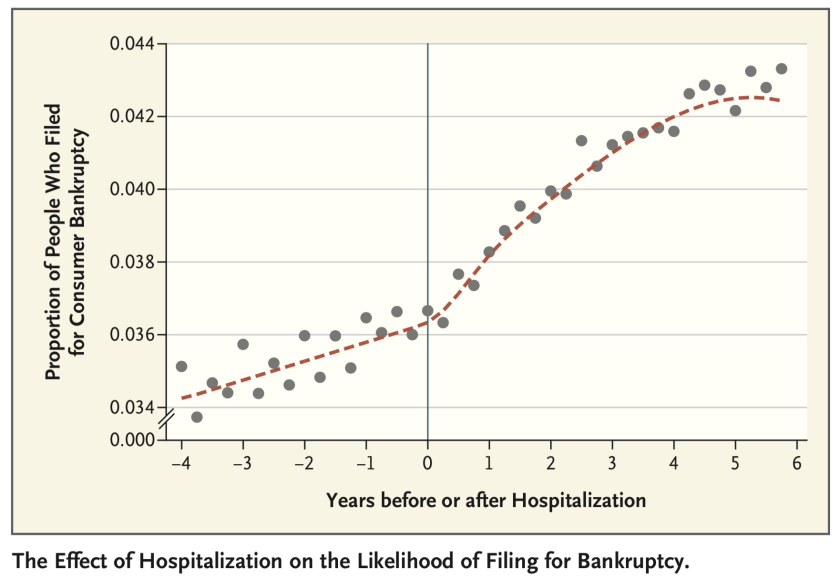

Last year, researchers from UC Santa Cruz, MIT and Northwestern took another crack at the data, examining the finances of patients who were admitted for treatment to California hospitals. They found “compelling evidence of the existence of medical bankruptcies but discovered that medical expenses cause many fewer bankruptcies than has been claimed” (by you-know-who). They estimated that “hospitalizations cause only 4% of personal bankruptcies among nonelderly U.S. adults.”

The dimensions of the debate should be evident by now. Himmelstein, Woolhandler and Warren have sturdily defended their methodology and findings.

Responding to Dranove and Millenson, they observed that narrowing the debts listed in bankruptcy filings to medical bills probably conceals the role of medical expenses in those cases. That’s because families may take intermediate steps to pay those bills before financially throwing in the towel. Responses by families themselves indicate that “medical debts that wound up as credit card balances, second mortgages, payday loans, collection lawsuits, and so on” are “some of the most important indicators of medical bankrupcies …. Medical debt often appears as ‘credit card debt’ or ‘mortgage’ in court records.”

As for the California data, Himmelstein, Woolhandler and Warren responded that the study was flawed in treating hospitalization as “the sole indicator of a medical problem that could lead to financial distress.” Families can be overwhelmed by nonhospitalization bills, including emergency care, physical therapy or prescriptions, not to mention the costs of treating chronic conditions that never result in a hospital stay but drain household accounts year in and year out. (The authors of the California study replied that relying on debtors’ own assessments “is not a credible way to estimate the causes of bankruptcy.”)

That’s where things stand right now. “At this point everyone agrees that many thousands of Americans suffer medical bankruptcies each year, but there’s still scholarly debate over exactly how many,” Himmelstein and Woolhandler wrote in response to the Post fact-checking. “Economists and business school professors (including some funded by the health insurance industry) generally offer lower estimates, and medical and legal researchers find higher numbers.”

Unquestionably, the individual burden of medical costs in the U.S. can be unsupportable and, in the richest country in the world, should be unnecessary. Sanders and Warren are right to point the finger at a dysfunctional healthcare financing system. Those who say things aren’t that bad are wrong; it’s worse. Debating whether the number of Americans forced into bankruptcy by medical debt is 500,000 or some other figure is nitpicking, and woefully beside the point. What everyone knows is that the threat is bad enough, and it can strike at anyone.