What Is 'Socialized Medicine'?: A Taxonomy of Health Care Systems

By Uwe E. Reinhardt

New York Times

Economix Blog

May 8, 2009, 6:48 am

With another “national conversation” about health reform upon us — as it is every decade or so — we will hear a lot of derisive talk about the evils of “socialized medicine.”

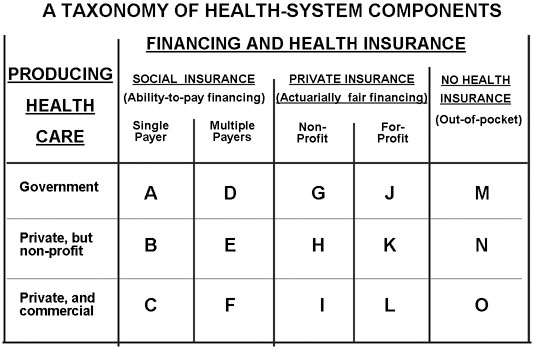

The term is regularly confused with “social health insurance,” which is not at all the same concept. The chart below may be helpful in appreciating the distinction.

Socialized medicine refers to health system in which the government owns and operates both the financing of health care and its delivery. Cell A in the chart represents socialized medicine.

Social health insurance, on the other hand, refers to systems in which individuals transfer their financial risk of medical bills to a risk pool to which, as individuals, they contribute taxes or premiums based primarily on ability to pay, rather than on how healthy or sick they are.

Socialized medicine is one form of social insurance. More typically, however, social insurance is coupled on the health-care delivery side with a mixture of government-owned facilities (e.g., municipal hospitals), private nonprofit hospitals (roughly 90 percent of all American hospital beds) or private for-profit facilities (investor-owned hospitals, private medical practices, pharmacies and so on). It follows that one cannot simply treat social insurance as socialized medicine. In principle, one could have social insurance with 100 percent private for-profit delivery facilities.

Under private commercial insurance, individuals also transfer the financial risk of bills for health care to a risk pool, but the premium the individual contributes to the risk pool reflects that individual’s health status. These premiums are, as actuaries put it, “medically underwritten” and “actuarially fair.” The risk pools under private insurance can be operated by not-for-profit or for-profit insurers. And like social insurance, private insurance typically is coupled with a mixed private and public delivery system.

In the chart, cells A, B, C jointly represent single-payer social insurance — e.g., traditional Medicare. Cells D, E, F jointly represent multiple-payer social insurance — e.g., Medicaid Managed Care. Cells G to L jointly represent individually purchased private insurance with actuarially fair premiums. Finally, cells M, N and O represent the uninsured or the cost-sharing portion of insured persons.

In between these distinct systems falls employment-based health insurance.

Large employers typically self-insure and use private insurers only to procure health care on behalf of employees (e.g., negotiate fees with the providers of health care) and administer claims. Other employers do not self-insure and instead purchase so-called group health insurance policies for all their employees jointly, as if they were one large family. The premium for a group policy is “experience rated” over the covered group of employees, which means that they reflect the average actuarial cost of all of one company’s employees.

The individual employee’s own contribution toward his or her employment-based insurance, however, is divorced from the individual’s (or the attached family’s) health status. In this sense, then, employment-based insurance could be described as “private social insurance,” as distinct from “government-run social insurance.”

Former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani of New York has exemplified the perennial confusion in this country over socialized medicine. In his ill-fated presidential bid, and subsequently as a supporter of Senator John McCain’s bid for the presidency, Mr. Giuliani routinely decried as socialized medicine (or “socialist”) any proposal presented by Democratic candidates, because typically the latter advocated tax-financed subsidies toward the purchase of health private insurance or expansions of public insurance programs. But technically none of them advocated socialized medicine.

Perhaps Mr. Giuliani was unaware that Americans all along the ideological spectrum reserve the purest form of socialized medicine — the V.A. health system — for the nation’s veterans. I find this cognitive dissonance amusing. Indeed, if socialized medicine is so evil, why didn’t Republicans privatize the V.A. health system when they controlled both the White House and the Congress during 2001-06?

Mr. Giuliani also seems to forget that, in 1996, he found social health insurance a perfect solution to the financial problems faced by former Mayor John V. Lindsay, who fell on financially hard times during the 1990s as a result of chronic illness.

In a fit of compassion, then Mayor Giuliani rushed to his friend’s assistance with — you guessed it — taxpayers’ money, rather than with a private sector solution. He did so by appointing Mr. Lindsay to two no-show city jobs that came with tax-financed municipal health insurance and a tax-financed pension.

It seems fair, then, to ask Mr. Giuliani why it was perfectly fine to bail out a financially distressed man who had been wealthy enough in his younger years to provide adequately for his old age, when proposals to extend the same kind of assistance to hard-working, uninsured members of lower-income families are decried by him as “socialism.”

One can only hope that our members of Congress and the typical American voter can make the right distinctions.

Uwe E. Reinhardt is an economics professor at Princeton.