By Sarah Kliff

The Washington Post, Wonk Blog, Oct. 30, 2012

There are a lot of big differences between health care in the United States and Canada. But when you look at how the two countries provide care for the elderly, it’s actually pretty similar. Both countries run an insurance plan for those over 64 that covers a defined set of benefits.

Canada has managed to provide those benefits, however, for a whole lot less. In this week’s Archives of Internal Medicine, David Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler look at the growth of spending on the elderly in the United States and Canada. It finds that, for the over 64 population, both in government programs, Medicare spending has grown significantly faster in the United States than in Canada.

Back in 1980, Medicare spent an average of $1,215 on each beneficiary. In Canada, that number stood at $2,141. The difference largely had to do with the level of benefits: Canadian health insurance covers about 80 percent of seniors’ medical costs, whereas Medicare covers about half. (More than 40 percent of Medicare beneficiaries will spend all assets on out-of-pocket costs during the last five years of life, according to one study.)

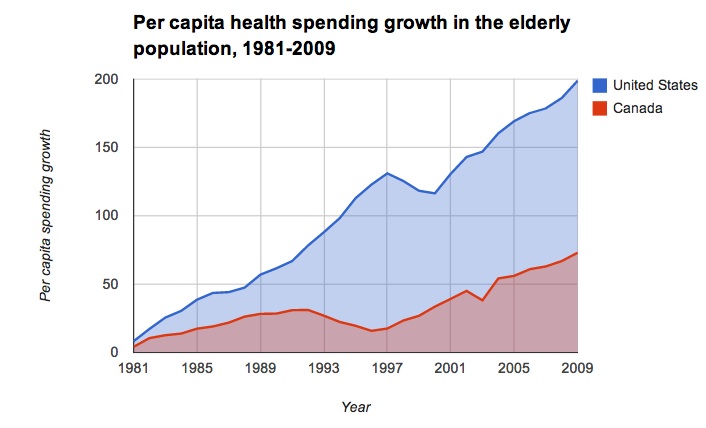

Since then, United States per capita spending has grown three times as quickly as it has in Canada. Here’s what that looks like in graph form, using data from the Himmelstein and Woolhandler study:

If American health spending on seniors had grown at the Canadian rate, Himmelstein and Woolhander estimate we would have spent $2.1 trillion less on Medicare benefits in the past three decades.

There are certain parts of the Canadian health-care system that would be pretty hard to replicate here in the United States.. One reason Canadian seniors’ coverage costs less is that they’re part of a universal coverage system, where everyone receives government-sponsored insurance. Having everyone in the same purchasing pool makes it easier for the government to negotiate lower rates. This also lowers administrative costs, as all health spending flows through one payer.

Medicare already has a lot of leverage in the United States, with over 50 million members. Getting even more leverage would mean adding more members — in other words, a more nationalized system like Canada’s.

Canada also works under a global budget for its health-care spending: It sets a finite amount that it’s willing to spend on medical care, and figures out how much it will pay doctors within those confines. The United States hasn’t usually been friendly to global budgets — there’s concern about coverage becoming too skimpy — although there is recent movement in this direction. Massachusetts recently became the first state to set a global cap on its health-care spending.

Himmelstein and Woolhandler point out that the Canadian system relies more on primary care doctors, who make up 51 percent of the physician population. In the United States, that number stands at 32 percent. “Primary care–centered health systems are,” they note, “Generally thriftier.”

That’s one change that could, theoretically, happen in the United States. It would, however, likely involve a trade-off, as fewer specialty doctors mean longer wait times to see a specialist. A Commonwealth Fund survey in 2010 found that 59 percent of respondents reported waiting more than four weeks for an appointment with a specialist, more than double the number in the United States.

This isn’t necessarily a trade-off on quality; Canada tends to do pretty well when it comes to international comparisons of health-care outcomes. It would, however, be a big change from how we deliver health care in the United States right now, with much easier access to speciality doctors.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/wp/2012/10/30/what-canada-can-teach-us-about-fixing-medicare/