This study, authored by PNHP president Adam Gaffney, M.D., M.P.H. and PNHP co-founders Steffie Woolhandler, M.D., M.P.H. and David Himmelstein, M.D. was published online in the International Journal of Health Services on June 9, 2020. Click HERE to read the study on the SAGE Journals website.

Abstract

While the COVID-19 pandemic presents every nation with challenges, the United States’ underfunded public health infrastructure, fragmented medical care system, and inadequate social protections impose particular impediments to mitigating and managing the outbreak. Years of inadequate funding of the nation’s federal, state, and local public health agencies, together with mismanagement by the Trump administration, hampered the early response to the epidemic. Meanwhile, barriers to care faced by uninsured and underinsured individuals in the US could deter COVID-19 care and hamper containment efforts, and lead to adverse medical and financial outcomes for infected individuals and their families, particularly for those from disadvantaged groups. While the US has a relatively generous supply of ICU beds and most other health care infrastructure, such medical resources are often unevenly distributed or deployed, leaving some areas ill-prepared for a severe respiratory epidemic. These deficiencies and shortfalls have stimulated a debate about policy solutions. Recent legislation, for instance, expanded coverage for testing for COVID-19 for the uninsured and underinsured, and additional reforms have been proposed. However comprehensive healthcare reform, e.g. via national health insurance, is needed to provide full protection to American families during the COVID-19 outbreak, and in its aftermath.

As of this writing, the United States is experiencing the world’s largest COVID-19 outbreak.1 Deaths are continuing to rise, and the hospital infrastructure of some cities has been severely strained. While every country faces unique challenges responding to this serious public health threat,2,3 the US’ underfunded public health infrastructure, fragmented medical care system, and paltry social protections have imposed particular impediments to control and mitigation of the epidemic.

As US policymakers contend with the widespread dissemination of COVID-19, addressing the structural weaknesses of the US public health and healthcare financing system — particularly for disadvantaged groups — must be a priority, both for this epidemic and the next. In this article, we explore how underfunding of the nation’s public health agencies impaired the early response to the epidemic; how financial barriers that obstruct care for many in the US healthcare system could hamper efforts to contain it moving forward; the adverse financial ramifications for patients from the outbreak; and potential policies to ameliorate health financing deficiencies in the months and years ahead.

1. Underfunded Public Health

Federal, state and local public health agencies are the frontline defense against novel epidemics. Years of inadequate funding of these agencies, however, has hampered the nation’s response to the outbreak.

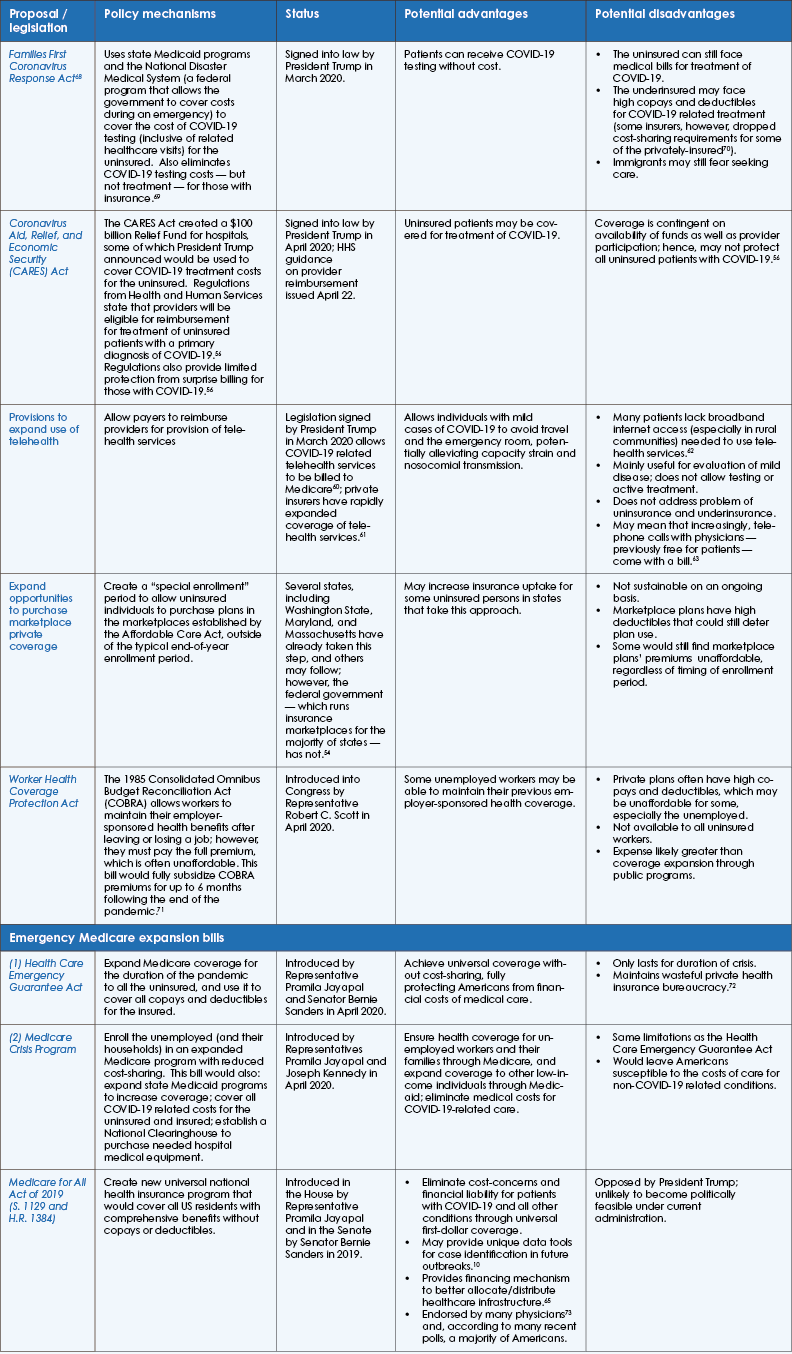

Despite nominal increases in public health spending over the past decade, there has been a progressive decline in such funding as a proportion of total health spending4 (Figure 1).5 Certain agencies and spending areas have seen particularly notable cuts. The budget of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), for instance, fell by about 10% (accounting for inflation) between 2010 and 2019, while CDC spending on state/local emergency preparedness fell by about a third from 2003 to 2019.6 The Prevention and Public Health Fund, a pool of public health funds established by the Affordable Care Act to help support state and local public health agencies, has seen multiple cuts since its creation.6 As budgets’ have grown tighter, state and local public health agencies have experienced a major decline in staffing, shedding some 50,000 personnel since 2008.7

Steps taken by the Trump administration further undercut the nation’s infectious disease readiness, including leaving some 700 staff position at the CDC unfulfilled during the 2017 hiring freeze8 and disbanding the office focused on federal pandemic preparedness.9 While the full story of the disastrous rollout of diagnostic testing has not yet been fully told, chronic underfunding of public health agencies appears to have left the nation ill-prepared for the arrival of the epidemic. For instance, case and contact tracing — measures that have been successfully deployed in nations such as Taiwan, South Korea, and Singapore,2,10 and that controlled the 2002-03 SARDS outbreak11-13 — were quickly abandoned in the US, as local health agencies became overwhelmed.14 Efforts to renew such efforts are currently underway in certain states, notably Massachusetts, but these are exceptions to the rule.

2. COVID-19 and Healthcare Affordability: Implications for Disease Control, Health, and Family Finances

In March 2020, as widespread dissemination of the novel coronavirus became obvious, case identification and contact tracing rapidly gave way to broad social distancing measures, including stay-at-home orders and closures of non-essential businesses, aimed at “flattening the epidemic curve.”3,15 Even if ultimately effective, epidemiologists predict that the outbreak will recrudesce once social distancing measures are eased, an eventuality that might be ameliorated or prevented through ramped up testing, case finding, and contact tracing. Such an intervention, however, requires a high-performing, and readily accessible, health system.2

Yet 30 million Americans, 9% of the population, had no health coverage before the epidemic,16 while 44 million more were underinsured — i.e. had coverage that required high copays, deductibles, or other out-of-pocket expenses.17 Overall, about a quarter of non-elderly adults were either uninsured, or avoided seeing a doctor in a given year because of costs, with (as shown in Figure 2) especially high rates in some states, such as Texas and Florida. As the economy spirals and millions of individuals are thrown out of work, the number of Americans uninsured or otherwise unable to afford care for COVID-19 will soar. News outlets carried stories early in the outbreak about patients with suspected coronavirus infections hit by “surprise” bills from hospitals, adding up to thousands of dollars.18-21 Although the widespread inaccessibility of coronavirus testing has thus far been the major bottleneck in the US, fear of costs could keep many infected patients from care in the future, hampering the case identification efforts needed to contain an outbreak. To address this likelihood, Congress passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, signed into law by President Trump on March 18. The law expands coverage of testing (and associated visits) both for the uninsured and those with copays and deductibles, which could alleviate such fears for some.

This measure, however, only covers the cost of testing — not treatment. As described in greater depth below, the Trump administration has also promised to use bailout funds to compensate hospitals for the costs of treated uninsured individuals with COVID-19. Such protection, however, is likely to be inadequate, and some individuals will no doubt still be deterred from obtaining medical care. Indeed, a poll conducted in early April found that 14% of Americans said they would avoid medical care due to cost if they developed symptoms consistent with COVID-19; the proportion was even higher among ethnic minorities and those with low incomes.22 Those who remain undiagnosed because they fear the financial consequences of a trip to the hospital may continue to go to work, attend school, or use public transportation, furthering spread. Lack of federally-mandated paid sick-leave is also likely to impede disease mitigations efforts. In 2019, about a quarter of civilian workers lacked paid sick leave, and the rate is substantially higher among those in service occupations.23 Staying home may not be financially tenable for some such individuals. As will be discussed later, new legislation expanded sick pay benefits for some American workers — but left millions out.

High healthcare costs could also threaten the health of patients infected with COVID-19. Fear of incurring out-of-pocket costs frequently deters patients from seeking urgently needed healthcare, even for “high-severity” conditions like acute asthma24 and myocardial infarction.25 Uninsured patients presenting to US emergency rooms with pneumonia or exacerbations of obstructive lung disease (potential COVID-19 symptoms) are more likely than those with insurance to be discharged home instead of admitted to hospital, likely reflecting patients’ desire to avoid ruinous bills and hospitals’ reticence to bear the costs of care.26 It is plausible that individuals with severe COVID-19 who nevertheless avoid medical care could suffer cardiopulmonary arrest in their homes. A surge in the number of patients found dead in their homes by paramedics in New York City during the outbreak suggests that many individuals with COVID-19 are dying before arriving to the hospital.27 However, it is unknown whether lack of healthcare access could have been a contributing factor in some or any of these deaths.

Yet even if inadequate coverage causes no physical harm, however, it can still inflict “financial toxicity.”28 For those with employer-sponsored insurance, the average cost of a hospitalization for pneumonia for patients with complications and co-morbidities was $20,292 in 2018, some of which may have to be paid out-of-pocket in the form of a deductible.29 Elderly patients with Medicare coverage, many on low fixed incomes, also face deductibles exceeding a $1,000 for a pneumonia hospitalization.30 Those facing severe protracted critical illness, however, may face even higher costs. A recent study found that out-of-pocket costs in the last year of life for the uninsured requiring ICU care averaged more than $26,000.31 Even for the insured these costs are often substantial, averaging $10,022 for those with private coverage.31 Such sums could be ruinous to the 4 in 10 US adults who are unable to cover even a $400 expense in the event of an emergency.32 Those unable to pay can face lawsuits, home foreclosure, and bankruptcy proceedings when hospitals seek to recover unpaid medical debts.33,34 And many individuals exposed to financial pressures from COVID-19-related medical costs may be forced to skimp on other important household expenses, such as rent or food, risking downstream deleterious health effects. For many, the financial harms of medical bills will be compounded by lost wages due to job loss, illness, or self-quarantine.

Epidemics tend also to have a disproportionate impact on oppressed populations.35 The H1N1 epidemic, for instance, led to higher hospitalization rates among racial/ethnic minorities relative to white populations,36,37 and a disproportionately high death rate among Hispanic children.37 Clear evidence is already mounting that Black and Hispanic are bearing the heaviest burden of severe COVID-19 disease and death as well.38,39 Yet Black and Hispanic Americans — and those with low-incomes more generally — are less likely to be insured,16 and have fewer household resources on average to cover the cost of copays and deductibles. At the same time, the Trump administration’s harsh anti-immigrant policies — including a recent rule change that deems immigrants to be “public charges” if they use public health programs, and hence potentially ineligible for upgrades in their immigration status — have sown fear in immigrant communities. These policies deter enrollment in health programs and could dissuade millions of immigrants from seeking care, including for COVID-19,40 despite the existence of an exemption for the care and treatment of communicable diseases.41 A 2018 survey, for instance, found that 13.7% of adults in immigrant families are avoiding participation in government benefit programs because they fear the consequences for their immigration status.42

Overall, the confluence of xenophobic policies, rising uninsurance, mass unemployment, and a major epidemic seems destined to exacerbate existing deep inequalities in health and healthcare.

3. COVID-19 and the Seriously Ill: Hospital Infrastructure and Affordability

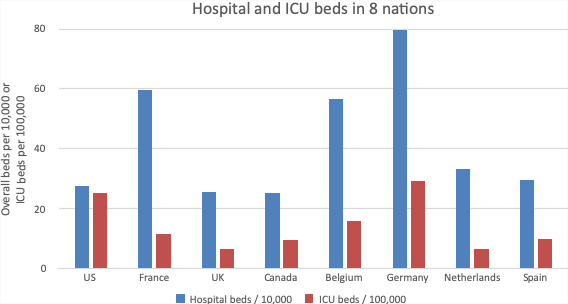

The fragmented and privatized US healthcare financing system also has distinct implications for those who develop severe illness from COVID-19. While the US is unique among high-income nations in its lack of universal coverage, it is less of an outlier with respect to its healthcare infrastructure. Figure 3 displays hospital and ICU bed supply in 8 nations in North America and Europe. On the one hand, the US is towards the lower end of peer nations with respect to bed supply. It has similar beds per capita as four of the nations in this sample (the United Kingdom, Canada, the Netherlands, and Spain), but substantially less than three (France, Belgium, and Germany). On the other hand, the US has a relatively generous supply of ICUs, with more ICU beds per capita than every nation in the sample except Germany. US ICU density — about 25 beds per 100,000 population depending on how it is counted — is more than twice that of France and Canada, and many-fold higher than the United Kingdom’s.43-47 Patients in US ICUs have, historically, been on average less severely ill than those in other nations as a consequence of this more generous supply,44,45 suggesting more surge capacity.48

Such aggregate statistics, however, obscure three potential problems. First, a large epidemic (with a rapid peak) could overwhelm (or severely strain) the hospital and ICU infrastructure of any nation49 — as in Italy50, New York, and potentially other US cities in coming weeks. Second, while the US’ laissez-faire approach to financing healthcare infrastructure has led to marked growth in ICU infrastructure51.52, it has also led to arbitrary regional imbalances in supply. There is a six-fold difference in ICU beds per capita between the hospital referral region with the highest and the lowest bed density in the US.43 As Carr, Addyson, and Kahn note, geographic variation in ICU density in the US means that a pandemic “could quickly exceed critical care capacity in some areas while leaving resources idle in others,” a reality that “reflects the limitations of a private health system in which planning occurs primarily from the hospital perspective.”43 This distributive problem reflects larger imbalances in the availability of healthcare infrastructure that stem from a profit-driven financing system, exemplified by ongoing hospital expansion in healthcare-dense areas, and the simultaneous closure of hospitals in rural and poorer areas. Consequently, while supply may be ample in some areas, it is inadequate in others in the face of an epidemic. Moreover, there are no mechanisms to redeploy resources to where they are needed, or to shift patients to less-stressed areas.

A lack of health planning, in other words, has left the nation’s healthcare system ill-prepared for an emergency, whether with respect to the distribution of infrastructure, or the stockpiling of ventilators or personal protective equipment for healthcare workers. And with no unified governance, federal, state, and local governments continue to compete with hospitals for supplies.

4. Potential policy solutions

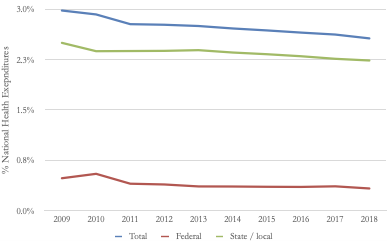

The challenge posed by COVID-19 in the context of these deficiencies in healthcare financing has prompted a range of reform proposals. The Table summarizes achieved and proposed reforms, as well as their benefits and limitations.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, signed into law by President Trump in March, provides coverage for the costs of diagnostic testing and related healthcare visits for the uninsured, as earlier noted.53 While this may encourage testing for such individuals, the law didn’t address the problem of high treatment costs (for instance, for those admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 pneumonia). The Act also required that all public and private insurers cover testing and related visits without cost-sharing,53 but, like the coverage of testing for the uninsured, does nothing to lower the far-higher out-of-pocket costs for treatment of COVID-19. Moreover, it’s unlikely to allay immigrants’ fears about enrolling in public health programs or seeking care.

Another initiative to cover the uninsured would allow uninsured individuals to purchase private plans outside of the typical “open enrollment” period, a step taken thus far by several states,54 although not yet by the federal government. Such a move might modestly increase insurance uptake, although coverage would remain unaffordable for many, including the millions of Americans rapidly joining the ranks of the uninsured.

A plan announced April 3 by the Trump administration would allocate a portion of the $100 billion in hospital relief provided by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, passed in late March, to cover costs of COVID-19 treatment for the uninsured.55 However, this program offers incomplete protection to patients: coverage is contingent both on the availability of funds and the participation of providers.56

Other provisions have been aimed at reducing medical costs for those with insurance. An announcement from the Internal Revenue Service that some plans with high-deductibles will be permitted (but not required) to exempt COVID-19-related care from the plan deductible57 might reduce out-of-pocket costs for some, but will likely have a limited effect. Additionally, some, but not all insurers, have announced plans to eliminate cost-sharing for COVID-19 related treatment, but many individuals will remain exposed to such costs absent federal action. Moreover, neither of these reforms does anything to address the problem of medical costs for other conditions, which will be increasingly unaffordable as workers lose jobs, income, and insurance benefits as recession deepens.

Addressing the lack of paid sick leave is also a policy priority. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act requires employers to provide workers with about 10 days of emergency sick leave, but it exempts the largest employers from the requirement, allows small employers to apply for exemptions, applies only to COVID-19 affected individuals, and expires at the end of 2020.58,59 Due to the exemptions, it might cover as few as 20% of American workers.58,59

A variety of other health financing reforms have been achieved or proposed to deal with the COVID-19 crisis. In early March, for instance, President Trump signed into law an $8.3 billion bill that increases funding for state and local health departments, vaccine and treatment development, medical supply purchases, and community health centers (CHC), clinics that provide care for substantial numbers of uninsured individuals.60 While the additional research and development funds will be useful — and might speed the development of useful therapeutics — the law did little to guarantee the affordability of treatments that emerge from the publicly-funded research.60 The new law also allows Medicare to pay providers for “telehealth” services, enabling remote electronic health visits from doctors that might unburden emergency rooms and reduce the risk of nosocomial coronavirus transmission. (Private insurers are also expanding coverage for telehealth services).61 But the effects of this provision are likely to be modest, particularly for poor patients, many of whom lack adequate internet access.62 Moreover, telehealth does little to allay patients’ cost concerns. Indeed, as phone conversation with physicians are increasingly re-classified as telehealth visits, some patients are finding that they face copays or deductibles for what may have been a previously free telephone call.63

Meanwhile, mounting job losses instigated by the epidemic and the ongoing public health measures taken to control it look likely to lead to enormous losses in health coverage: an estimated 7.3 million workers could become uninsured by June 1 if predicted unemployment increases come to fruition.64 In response, lawmakers have proposed additional reforms to expand coverage to this population. A bill introduced by House Democrats in April 2020, for instance, would provide full subsidization of COBRA plans, which would allow many individuals to maintain their employer-sponsored health benefits after job loss. Such a reform, however, would exclude many of the uninsured, while doing nothing to protect out-of-work individuals form the high copays and deductibles imposed by many employer-sponsored private plans.

Others have proposed using the Medicare program to expand coverage during the crisis. In April, Representative Pramila Jayapal and Senator Bernie Sanders introduced the Health Care Emergency Guarantee Act, which would expand Medicare coverage to all the uninsured, and simultaneously provide wrap-around coverage of copays and deductibles for the insured. Later that month, Jayapal joined Massachusetts Representative Joseph Kennedy in introducing the Medicare Crisis program, a more limited bill that would provide Medicare coverage to the unemployed, bolster state Medicaid programs, and cover all COVID-19 related care costs. Both proposals, particularly the more comprehensive Health Care Emergency Guarantee Act, would realize major expansions of coverage, protecting millions of Americans from burdensome healthcare costs for the duration of the crisis.

While many of these proposals, especially the emergency Medicare expansions, could provide some aid to those affected by COVID-19, full protection, in the long-term, would require would systemic reform. Addressing financing dysfunctions on a disease-by-disease basis, after all, is neither efficient nor fair. The COVID-19 outbreak hence serves as a reminder of the benefits of a unified, national health program. A Medicare for All reform, much discussed in Democratic presidential primary debates, would achieve universal coverage and address the problem of underinsurance. Such a reform might have additional advantages specific to an outbreak of an infectious disease. For instance, it could provide public health authorities with novel tools to combat epidemics, such as Taiwan’s use of its national health insurance database for case finding early in the epidemic.10 A well-structured national health insurance reform would also facilitate moving to a more rational and equitable allocation of ICUs and other healthcare resources65 through health planning and the public-financing of hospital capital expansion. This could help ensure an adequate supply and distribution of resources in the face of future epidemics. At the same time, the nation needs to dramatically increase funding of its public health agencies. A doubling of funding — from around 2.5% of national health expenditures to 5.0% — will not end the current epidemic, but it could help ensure readiness for the next one.66

“Epidemics,” wrote the German pathologist Rudolf Virchow, “are like large sign-posts from which statesman of stature can read that a disturbance has occurred in the development of his [sic] nation.”67 (pp. 22) COVID-19 is such a sign-post. The outbreak has already exposed the multifold inadequacies of the US’ uniquely unequal, privatized and fragmented health financing system. It also illuminates other inequities — including exclusionary policies that deter immigrants from using social assistance programs, lack of universal paid sick leave, and inadequate protections for workers — that weaken our social fabric and endanger the public’s health. As of this writing, it is unclear how severe the COVID-19 outbreak will ultimately prove to be in the US, although the rapidly climbing death toll is already a tragedy. Whatever the future holds, however, the transformation of the nation’s healthcare system and social safety-net is urgently needed.

Table: Legislation, policies, and proposals to address health financing challenges related to COVID-19

Click HERE to view a high-res PDF of this table.

Figure 1: Public Health Spending as a Percent of National Health Expenditures: 2009 – 2018

Source of data: National Health Expenditures Accounts, 2009-2018.5

Figure 2: Inadequately insured non-elderly adults by state (%)

Source: Author’s analysis of the 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Inadequately insured include those who are uninsured, or those who are insured but failed to see a doctor when needed due to cost. Includes adults 18 – 64 years in age. Map created with Microsoft Excel. Inadequate insurance rate for states not shown: Hawaii – 14%; New Hampshire – 18%; Massachusetts — 16%; Connecticut – 17%; Rhode Island – 19%; New Jersey – 22%; Delaware – 22%; Maryland – 19%; District of Columbia – 13%.

Figure 3: Hospital and ICU Bed Supply in 8 Nations

Notes: Hospital beds / 10,000 population are from OECD74 (2016 for the US and 2017 for other nations). ICU beds for the United States is drawn from Wallace et al.47, who reported 77,809 beds in 2009; total population denominator for that year (306,771,529) is drawn from the US Census. ICU beds for Canada is for 2009-10 and is drawn from Fowler et al.; these beds only include those with capacity for mechanical ventilation.46 ICU beds for European nations are drawn from Rhodes et al., and reflect years 2010-11; they include “intermediate care beds” and hence may overstate capacity relative to the US and Canada.75 Of note, the ICU bed supply in these 8 nations were also studied by Wunsch et al., who found roughly similar figures for most nations in 2005 (albeit with a substantial increase over time in the UK);44 we selected these same nations for presentation here for consistency.

References

- Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed April 5, 2020.

- Legido-Quigley H, Asgari N, Teo YY, et al. Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? The Lancet. March 2020. https://www.thelancet.com… Accessed March 7, 2020.

- Anderson R, Heestereek H, Klinkenberg D, Hollingsworth TD. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? The Lancet. 2020.

- Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Public Health’s Falling Share of US Health Spending. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):56-57. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302908

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National Health Expenditures by type of service and source of funds, CY 1960-2018. https://www.cms.gov… Accessed April 2, 2020.

- The Impact of Chronic Underfunding of America’s Public Health System: Trends, Risks, and Recommendations, 2019. tfah. https://www.tfah.org… Accessed April 2, 2020.

- Leider JP, Coronado F, Beck AJ, Harper E. Reconciling Supply and Demand for State and Local Public Health Staff in an Era of Retiring Baby Boomers. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(3):334-340. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2017.10.026

- Sun L. Nearly 700 vacancies at CDC because of Trump administration’s hiring freeze. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com… Accessed April 2, 2020.

- Cameron B. President Trump closed the White House pandemic office. I ran it. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com… Published March 13, 2020. Accessed April 2, 2020.

- Wang CJ, Ng CY, Brook RH. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: Big Data Analytics, New Technology, and Proactive Testing. JAMA. March 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3151

- Fraser C, Riley S, Anderson RM, Ferguson NM. Factors that make an infectious disease outbreak controllable. PNAS. 2004;101(16):6146-6151. doi:10.1073/pnas.0307506101

- Hellewell J, Abbott S, Gimma A, et al. Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. The Lancet Global Health. 2020;0(0). doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30074-7

- Wilder-Smith A, Chiew CJ, Lee VJ. Can we contain the COVID-19 outbreak with the same measures as for SARS? The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;0(0). doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30129-8

- Dolan J, Mejia B. L.A. County gives up on containing coronavirus, tells doctors to skip testing of some patients. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com… Published 2020. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- Parodi SM, Liu VX. From Containment to Mitigation of COVID-19 in the US. JAMA. March 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3882

- Cohen RA, Terlizzi EP, Martinez ME. Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey, 2018. National center for health statistics; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov… Accessed August 20, 2019.

- Collins SR, Bhupal HK, Doty MM. Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured. Commonwealth Fund; 2019. https://www.commonwealthfund.org… Accessed November 25, 2019.

- Kliff S. Kept at the Hospital on Coronavirus Fears, Now Facing Large Medical Bills. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com… Published March 2, 2020. Accessed March 5, 2020.

- Conarck B. A Miami man who flew to China worried he might have coronavirus. He may owe thousands. Miami Herald. https://www.miamiherald.com… Published February 24, 2020. Accessed March 5, 2020.

- Abrams A. Total Cost of Her COVID-19 Treatment: $34,927.43. Time. https://time.com… Accessed March 22, 2020.

- Rosenthal E, Huetteman E. He Got Tested for Coronavirus. Then Came the Flood of Medical Bills. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com… Published March 30, 2020. Accessed March 31, 2020.

- Inc G. In U.S., 14% With Likely COVID-19 to Avoid Care Due to Cost. Gallup.com. https://news.gallup.com… Published April 28, 2020. Accessed April 28, 2020.

- Employee Benefits in the United States – March 2019. Bureau of Labor Statistics https://www.bls.gov… Accessed March 9, 2020.

- Wharam JF, Zhang F, Landon BE, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. Low-socioeconomic-status enrollees in high-deductible plans reduced high-severity emergency care. Health Affairs. 2013;32(8):1398-1406. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1426

- Smolderen KG, Spertus JA, Nallamothu BK, et al. Health care insurance, financial concerns in accessing care, and delays to hospital presentation in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(14):1392-1400. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.409

- Venkatesh AK, Chou S-C, Li S-X, et al. Association Between Insurance Status and Access to Hospital Care in Emergency Department Disposition. JAMA Intern Med. April 2019. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0037

- Winter T. “Cardiac calls” to 911 in New York City surge, and they may really be more COVID cases. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com… Accessed April 29, 2020.

- Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. The oncologist. 2013;18(4):381-390. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279

- Potential costs of coronavirus treatment for people with employer coverage. Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org… Accessed March 22, 2020.

- Damico A, 2020. How Much Could Medicare Beneficiaries Pay For a Hospital Stay Related to COVID-19? The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. March 2020. https://www.kff.org… Accessed April 2, 2020.

- Khandelwal N, White L, Curtis JR, Coe NB. Health Insurance and Out-of-Pocket Costs in the Last Year of Life Among Decedents Utilizing the ICU. Critical Care Medicine. 2019;47(6):749. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000003723

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2018.; 2019:64. https://www.federalreserve.gov… Accessed March 4, 2020.

- Lucas JH Elizabeth. ‘UVA Has Ruined Us’: Health System Sues Thousands Of Patients, Seizing Paychecks And Claiming Homes. Kaiser Health News. September 2019. https://khn.org… Accessed November 22, 2019.

- Himmelstein DU, Lawless RM, Thorne D, Foohey P, Woolhandler S. Medical Bankruptcy: Still Common Despite the Affordable Care Act. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(3):431-433. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304901

- DeBruin D, Liaschenko J, Marshall MF. Social justice in pandemic preparedness. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(4):586-591. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300483

- Information on 2009 H1N1 Impact by Race and Ethnicity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. https://www.cdc.gov… Accessed March 3, 2020.

- Dee DL, Bensyl DM, Gindler J, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in hospitalizations and deaths associated with 2009 pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) virus infections in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(8):623-630. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.03.002

- Radio BF Nashville Public. Long-Standing Racial And Income Disparities Seen Creeping Into COVID-19 Care. Kaiser Health News. April 2020. https://khn.org… Accessed April 6, 2020.

- Garg S. Hospitalization Rates and Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Laboratory-Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 — COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3

- Zallman L, Finnegan KE, Himmelstein DU, Touw S, Woolhandler S. Implications of Changing Public Charge Immigration Rules for Children Who Need Medical Care. JAMA Pediatr. July 2019:e191744-e191744. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1744

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Public Charge. USCIS. https://www.uscis.gov… Published March 13, 2020. Accessed March 15, 2020.

- Bernstein H, Gonzalez D, Karpman M, Zuckerman S. One in Seven Adults in Immigrant Families Reported Avoiding Public Benefit Programs in 2018. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org… Published May 20, 2019. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- Variation in Critical Care Beds Per Capita in the United States: Implications for Pandemic and Disaster Planning. JAMA. 2010;303(14):1371-1372. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.394

- Wunsch H, Angus DC, Harrison DA, et al. Variation in critical care services across North America and Western Europe. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(10):2787-2793, e1-9. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186aec8

- Wunsch H, Angus DC, Harrison DA, Linde-Zwirble WT, Rowan KM. Comparison of Medical Admissions to Intensive Care Units in the United States and United Kingdom. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2011;183(12):1666-1673. doi:10.1164/rccm.201012-1961OC

- Fowler RA, Abdelmalik P, Wood G, et al. Critical care capacity in Canada: results of a national cross-sectional study. Crit Care. 2015;19:133. doi:10.1186/s13054-015-0852-6

- Wallace DJ, Angus DC, Seymour CW, Barnato AE, Kahn JM. Critical Care Bed Growth in the United States. A Comparison of Regional and National Trends. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;191(4):410-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.201409-1746OC

- Wunsch H, Wagner J, Herlim M, Chong DH, Kramer AA, Halpern SD. ICU occupancy and mechanical ventilator use in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(12):2712-2719. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318298a139

- Toner E, Waldhorn R. What Hospitals Should Do to Prepare for an Influenza Pandemic. Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science. 2006;4(4):397-402. doi:10.1089/bsp.2006.4.397

- Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? The Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9

- Halpern NA, Pastores SM. Critical care medicine in the United States 2000-2005: an analysis of bed numbers, occupancy rates, payer mix, and costs. Critical care medicine. 2010;38(1):65-71. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b090d0

- Halpern NA, Pastores SM, Greenstein RJ. Critical care medicine in the United States 1985-2000: an analysis of bed numbers, use, and costs. Critical care medicine. 2004;32(6):1254-1259.

- Adler MF Christen Linke Young, and Loren. What are the health coverage provisions in the House coronavirus bill? Brookings. March 2020. https://www.brookings.edu… Accessed March 15, 2020.

- McIntire ME, Clason L. States reopen insurance enrollment as coronavirus spreads. Roll Call. https://www.rollcall.com… Accessed March 15, 2020.

- Stephanie A. Trump Administration to Pay Hospitals to Treat Uninsured Coronavirus Patients; Hospitals would have to agree not to bill patients or issue unexpected charges – ProQuest. Wall Street Journal. https://search-proquest-com… Published April 3, 2010. Accessed April 5, 2020.

- Update on COVID-19 Funding for Hospitals and Other Providers. The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. April 2020. https://www.kff.org… Accessed April 28, 2020.

- IRS: High-deductible health plans can cover Coronavirus costs. Internal Revenue Service. https://www.irs.gov… Accessed March 11, 2020.

- Board TE. Opinion. There’s a Giant Hole in Pelosi’s Coronavirus Bill. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com… Published March 14, 2020. Accessed March 15, 2020.

- Lowey NM. Text – H.R.6201 – 116th Congress (2019-2020): Families First Coronavirus Response Act. https://www.congress.gov… Published March 14, 2020. Accessed March 15, 2020.

- 6 things to know about the coronavirus funding package. POLITICO. https://www.politico.com… Accessed March 9, 2020.

- Cohen JK. New telemedicine strategies help hospitals address COVID-19. Modern Healthcare. https://www.modernhealthcare.com… Published March 6, 2020. Accessed March 10, 2020.

- Drake C, Zhang Y, Chaiyachati KH, Polsky D. The Limitations of Poor Broadband Internet Access for Telemedicine Use in Rural America: An Observational Study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(5):382. doi:10.7326/M19-0283

- Hancock J. Telehealth Will Be Free, No Copays, They Said. But Angry Patients Are Getting Billed. Kaiser Health News. April 2020. https://khn.org… Accessed April 28, 2020.

- Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. Intersecting U.S. Epidemics: COVID-19 and Lack of Health Insurance. Ann Intern Med. April 2020. doi:10.7326/M20-1491

- Gaffney A, Waitzkin H. Policy, Politics, and the Intensive Care Unit. In: Civetta, Taylor & Kirby’s Critical Care. Fifth.; :11.

- Gaffney A, Physicians for a National Health Program. Eight Needed Steps in the Fight Against COVID-19. Boston Review. http://bostonreview.net… Published April 2, 2020. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- Virchow R. Collected Essays on Public Health and Epidemiology. Vol 1. (Rather LJ, ed.). Canton, MA: Science History Publications, U.S.A.; 1985.

- Dawson L, Long M, Mar 23 KPP, 2020. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act: Summary of Key Provisions. The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. March 2020. https://www.kff.org… Accessed April 2, 2020.

- H.R. 6201, Families First Coronavirus Response Act: Title-By-Title Summary. https://appropriations.house.gov…

- Simmons-Duffin S. Some Insurers Waive Patients’ Share Of Costs For COVID-19 Treatment. NPR.org. https://www.npr.org… Accessed April 28, 2020.

- The Worker Health Coverage Protection Act. Committee on Education & Labor Summary. https://edlabor.house.gov… Accessed April 28, 2020.

- Himmelstein DU, Campbell T, Woolhandler S. Health Care Administrative Costs in the United States and Canada, 2017. Ann Intern Med. January 2020. doi:10.7326/M19-2818

- Crowley R, Daniel H, Cooney TG, Engel LS, for the Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Envisioning a Better U.S. Health Care System for All: Coverage and Cost of Care. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(2_Supplement):S7. doi:10.7326/M19-2415

- OECD Statistics: Health Care Resources. https://stats.oecd.org… Accessed March 7, 2020.

- Rhodes A, Ferdinande P, Flaatten H, Guidet B, Metnitz PG, Moreno RP. The variability of critical care bed numbers in Europe. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(10):1647-1653. doi:10.1007/s00134-012-2627-8