By Lambert Strether of Corrente

Naked Capitalism, September 27, 2021

Alert reader Carla brought Direct Contracting Entities (DCEs) to my attention in comments here. She in turn had been informed by a webinar from PNHP, the long-time single payer advocates. As it turns out, DCEs grow in the same polluted soil as the Democrats’ previous privatization attempt, the Geographic Contracting model, now on hold, after a public outcry. However, DCEs are complicated to explain, because our health care system is run by greedy sociopathic members of the professional managerial class, who complicate matters deliberately, partly for fun, but mostly for profit [1].

Because personnel is policy, I’m going to start with Liz Fowler who, at least nominally animated by an ideology called Value-Based Care (VBC), is using her position as Director of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service (CMS) within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), to impose a “payment model” called “Direct Contracting Entities” on the majority of “traditional” Medicare recipients, thereby privatizing it. (Medicare Advantage is already privatized.) Each of those italicized topics will get its own heading, below. I’ll use a simple Q&A format, where the questions are in the form “Who is Liz Fowler?” and answers are in the form “Liz Fowler [family blog]s.” The simple structure works because the entire CMMI structure should be razed and the ground salted, so nothing like it ever happens again. It won’t be, so I’m going into detail so that when CMMI comes up with its next privatization scam, you’ll be able to recognize the moving parts. So to Liz Fowler.

Liz Fowler

Who is Liz Fowler? Here is Fowler’s official biography:

Elizabeth Fowler, J.D., Ph.D., is the director of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) and deputy administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Prior to joining the Biden administration, she was Executive Vice President for Programs at the Commonwealth Fund. Before joining the Fund, Dr. Fowler served as Vice President for Global Health Policy at Johnson & Johnson. In that role, she focused on health care delivery system and payment reform in the U.S. and health care systems and reform in emerging markets. Prior to that position, she was a special assistant to President Barack Obama on health care and economic policy at the National Economic Council, and occupied key positions at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, where she assisted with implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Prior to her work in the administration, Dr. Fowler was Chief Health Counsel to former Senate Finance Committee Chair, Senator Max Baucus, served as Vice President of Public Policy and External Affairs for WellPoint, Inc. (now Anthem).

Liz Fowler [family blog]s. As we wrote earlier this year, unknowingly translating the above:

Ah, Liz Fowler. An old friend and an especially scaly Flexian who makes Jon Gruber look like a cute little gecko:

When the legislation that became known as “Obamacare” was first drafted, the key legislator was the Democratic Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, Max Baucus, whose committee took the lead in drafting the legislation. As Baucus himself repeatedly boasted, the architect of that legislation was Elizabeth Folwer, his chief health policy counsel; indeed, as Marcy Wheeler discovered, it was Fowler who actually drafted it… What was most amazing about all of that [or not] was that, before joining Baucus’ office as the point person for the health care bill, Fowler was the Vice President for Public Policy and External Affairs (i.e. informal lobbying) at WellPoint, the nation’s largest health insurance provider (before going to WellPoint, as well as after, Fowler had worked as Baucus’ top health care aide). … More amazingly still, when the Obama White House needed someone to oversee implementation of Obamacare after the bill passed, it chose . . . Liz Fowler. Now, as Politico’s “Influence” column briefly noted on Tuesday, Fowler is once again passing through the deeply corrupting revolving door as she leaves the Obama administration to return to the loving and lucrative arms of the private health care industry: “Elizabeth Fowler is leaving the White House for a senior-level position leading ‘global health policy’ at Johnson & Johnson’s government affairs and policy group.”

Having Fowler involved in anything is a terrible sign; she’s as corrupt as they come [2]. One of the things she’s enmeshed in at CMMI is Value-Based Care, to which we now turn.

Value-Based Care

What is Value-Based Care?. The concept seems to have gained its first prominence at Harvard Business School in 2006, but here is how the New England Journal of Medicine defined it in 2017:

Value-based healthcare is a healthcare delivery model in which providers, including hospitals and physicians, are paid based on patient health outcomes. Under value-based care agreements, providers are rewarded for helping patients improve their health, reduce the effects and incidence of chronic disease, and live healthier lives in an evidence-based way.

Value-based care differs from a fee-for-service or capitated approach, in which providers are paid based on the amount of healthcare services they deliver. The “value” in value-based healthcare is derived from measuring health outcomes against the cost of delivering the outcomes.

Which sounds reasonable enough, even if you know how slippery the word “value” can be. The key point is that “fee for service” (FFS) is not the payment model under VBC. Value is. However–

Value-Based Care [family blog]s. Ask yourself: How will determining value be operationalized within a payments system? The answer will be to develop a taxonomy of what is valued, and then code for it and bill on the coding, case by case. Hold onto that thought for when we get to DCEs. Meanwhile, Liz Fowler’s ideology is Value-Based Care:

During her opening plenary at the National Association of ACOs Spring 2021 Conference, Liz Fowler, PhD, JD, deputy administrator and director of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, highlighted how the center is taking a pause to reassess its models and determine what is coming next.

“I want to make clear that our commitment to value-based care has never been stronger,” Fowler said.

This brings us to the CMMI, the institutional setting in which Value-Based Care is being pursued.

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation

What is the CMMI? To begin with, people at Fowler’s level believe that ObamaCare was passed to deliver not merely “access” to health care, but access to value-based health care, and that CMMI was to be the instrument for this. Once more from Fowler’s ACO plenary:

In addition to providing insurance for the uninsured, the goal of the Affordable Care Act was to move away from fee-for-service to value-based care. Although strides have been made, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) is taking time to reassess its portfolio of payment models.

Expanding on the concept of “payment models,” from Kaiser Family Foundation’s CMMI FAQ:

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), also known as the “Innovation Center,” was authorized under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and tasked with designing, implementing, and testing new health care payment models to address growing concerns about rising costs, quality of care, and inefficient spending. Congress specifically directed CMMI to focus on models that could potentially lower health care spending for Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) while maintaining or enhancing the quality of care furnished under these programs. CMMI is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and is managed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

In other words, “because markets“; there is no alternative to them. CMMI is “taking time” to “reassess” its models because, well–

The CMMI [family blog]s. The GAO reported on the CMMI’s efforts in 2018. As we wrote:

Beyond noting that only 2 of the 37 “Innovation” Center models were worth expanding, GAO assessed the Center by the three goals it had set up for itself. Page 54 et seq:

Goal 1: Reduce the growth of healthcare costs while promoting better health and health care quality through delivery system reform This goal has three performance measures that focus on ACOs. As shown in table 3, the Innovation Center has reported mixed results in achieving the targets set. For the remaining measure—the percentage of ACOs that shared in savings—the center did not meet its target during either of the two years for which data were available. …

Goal 2: Identify, test, and improve payment and service delivery models. This goal has one performance measure, which identifies the number of models that currently indicate (1) cost savings while maintaining or improving quality or (2) improving quality while maintaining or reducing cost. As of September 30, 2016, the Innovation Center reported that four [of 37] section 1115A model tests have met these criteria (see table 4).

Goal 3: Accelerate the spread of successful practices and models. For this goal, the first performance measure focuses on the number of states developing and implementing a health system transformation and payment reform plan. The second measure focuses on increasing the percentage of active model participants who are involved in Innovation Center or related learning activities. As shown in table 5, the Innovation Center reported meeting its target for the first measure for both fiscal years 2015 and 2016, but not meeting its target for the second measure.

And concluding, with the woo-woo noises at last becoming audible:

Looking forward, officials told us that the Innovation Center has developed a methodology to estimate a forecasted return on investment for the model portfolio, and is in the early stages of refining the methodology and applying it broadly across the portfolio in 2018. As part of the development efforts, the Innovation Center expects to utilize standard investment measures used in the public and private sectors.

Whatever that means. Since we don’t know what a model is, what on earth is the use of creating a portfolio of them?

The situation has not improved since then, as Bill Frist (!!) writes (“only five of the 54 models delivered substantial financial savings. The majority have not saved money, and several are on pace to lose billions of dollars”) and as Fowler in her plenary admits:

Fowler worries that over the past decade since CMMI was established, the stakeholders have reached no consensus about what, specifically, the center should be achieving. Some of the questions that need to be answered are as follows:

- Are cost savings the most important measure of success, or is quality improvement just as important?

- Is risk bearing among providers the key to unlocking value?

- Should CMMI’s goal be to expand a model so it becomes a permanent part of Medicare, or is health care transformation the ultimate goal?

The ACA funded CMMI $10 billion from 2011 through 2019, and another $10 billion for each decade after that. These funds were not subject to the appropriations process. For that amount of money, we’re still asking questions like that?

Nevertheless, the CMMI wields enormous power, because through it, HHS can implement payment models without Congressional authorization. One such payment model is the “Direct Contracting Entity,” to which we now turn.

Direct Contracting Entities

What are Direct Contracting Entities? As defined by one DCE player, Pearl Health:

DCEs enable participants to transition their Traditional Medicare populations to value-based care via a capitated reimbursement model, creating a predictable flow of revenue, and the opportunity to generate shared savings, creating incentives for providing more efficient care.

Seems reasonable enough. Venture capitalists Andreessen Horowitz are a bit more expansive:

One of the hallmarks of value-based care is a shift away from reactive, fee-for-service models and toward prospective payment models. Direct contracting is a model where large holders of risk — like self-funded employers and health plans — contract directly with a narrow set of provider groups and health systems [3] for a specific population and a defined set of services [4]. This can look as simple as contracting with a handful of health systems to provide all-inclusive care bundles for joint surgery, to something as broad-reaching as establishing an Accountable Care Organization (ACO) for the comprehensive care of a patient population in a given region. Because both parties share in accountability and responsibilities across cost, care coordination, and outcomes, models like these represent a major step in the transition toward value-based care.

These CMS Direct Contracting programs represent a key step forward by driving increased access to value-based care for the Medicare Fee-for-Service group of beneficiaries. And importantly, they create a range of new opportunities for new entrants by 1) substantially broadening the range of care organizations that can participate in these models (including new entrants that previously would have been ineligible) and 2) granting increased flexibility on the benefits design and patient care initiatives that can be offered, thus creating unique opportunities for new entrants that offer care solutions that can ultimately drive higher-value care (but would have not been within scope or incentivized with traditional Medicare Fee-For-Service).

Translating: “[D]riving increased access to value-based care” means the elimination of fee-for-service care. More importantly, “new entrants that previously would have been ineligible” means, for example, private equity or “big tech,” Presumably why Andreessen Horowitz is taking a look at the field of play. I shudder to think what “unique opportunities for new entrants” could mean. Uber for kidneys? Unfortunately for us all–

DCEs [family blog]. Let’s work through the “unique opportunities.” First, from PNHP, today there are 53 DCEs (with new openings temporary closed). 28 are investor-owned. 6 are insurer-based. The 6 insurer-based DCEs “operate in 19 states that have 57% of the entire national FFS population.” If DCEs can move those all those FFS patients customers to VBC, that would mean 57% of $660 billion in Medicare spending by 2025 ($330 billion in 2019). How would the DCEs do that? They would sign up doctors, and that would bring the del>patients customers along. Again PNHP:

Doctors are lured to participate in a DCE by promises of up to a 40% increase in provider Medicare reimbursement

and a reduced set of core quality measures they have to meet. Once doctors sign up, their patients are automatically “aligned” to the DCE without patients’ knowledge or consent; patients are sent a letter, which they are not likely to read or understand.

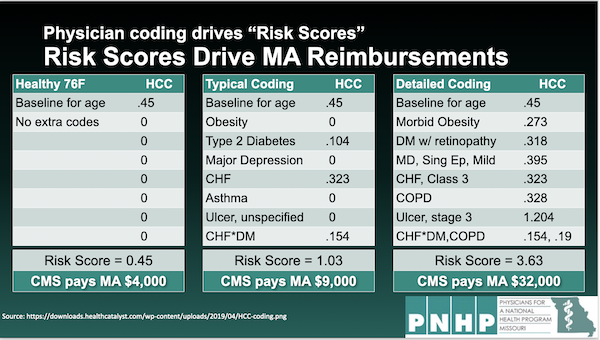

And you can bet the DCE won’t help them understand. But wait! There’s more! The DCEs are money machines, and not just because of revenues from patient care. They are money machines because — this is why I asked you to hold that thought on coding — value-based care is a phishing equilibrium for upcoding. (In the vulgate: If fraud can occur, it will already have occurred. See NC here and here on medical upcoding.) Here is a worked example from Ed Weisbart of PNHP:

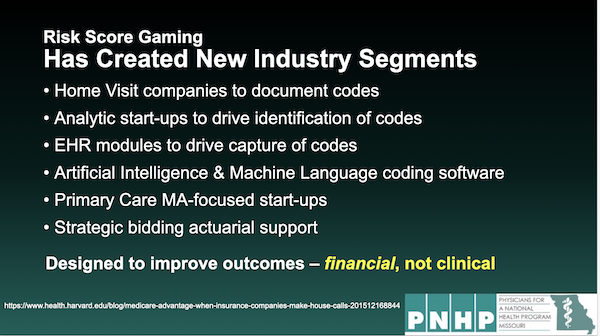

Note how the different codes — all for the same patient! — drive the bottom line; see at “CMS pays.” In fact, there’s an entire industry line of business devoted to gaming medical codes for profit:

(It’s really beautiful that AI is being used for fraud. But indeed, why not?) So, to review, DCEs allow insurance companies and investor-owned entities to put the entire Medicare fee-for-service system in their crosshairs, capturing 67% of the existing “traditional Medicare population,” most of them without informed consent, using them as human fodder for upcoding fraud, and all without congressional authorization or review of any kind. If that’s not privatization I don’t know what is. I guess this is sort of thing is why Hillary Clinton said single payer would “never, ever” come to pass [5]. Whaddaya know. Thanks, Liz!

Conclusion

Obviously, there are a great many layers of obfuscation to the DCE privatization scam, and I hope I got them right. Please correct me where I have gone wrong. (Here is Weisbart’s PowerPoint presenation; medical back office mavens will be able to understand it better than I can.)

Finally, there is a petition: Consider signing it. The Geographic Contracting model was stopped; DCEs can be stopped.

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com…

Notes

- In the Before Times, I would have been much more polite. But here we are.

- Back when Obama was shilling for the Affordable Care Act, he did a series of town halls on health care policy, to which I listened. The post on the town hall has long ago succumbed to link rot, but I remember that a PNHP doctor with whom I was familiar actually managed to ask Obama a question on single payer. I forget what Obama answered, but the fact of the question itself was remarkable (given that Max Baucus refused to allow single payer advocates at his hearings, and had them arrested when they protested). The White House had an intern out of Fowler’s office doing a live blog. When I checked, the single payer question had been censored.

- Sounds like an opportunity for in-and-out-of network gaming, to me.

- Ditto.

- This also explains why Biden but a non-entity like Becarra in charge of HHS (aside from the payoff to the California oligarchy). Alex Azar, shark though he was, would have understood this play. Becarra is a babe in the woods with no health care experience, and won’t.