By Joseph White

Case Western Reserve University

The Milbank Quarterly

Volume 85, Number 3, 2007

Many studies arguing for or against markets to finance medical care investigate “market-oriented” measures such as cost sharing. This article looks at the experience in the American medical marketplace over more than a decade, showing how markets function as institutions in which participants who are self-seeking, but not perfectly rational, exercise power over other participants in the market. Cost experience here was driven more by market power over prices than by management of utilization. Instead of following any logic of efficiency or equity, system transformations were driven by beliefs about investment strategies. At least in the United States’ labor and capital markets, competition has shown little ability to rationalize health care systems because its goals do not resemble those of the health care system most people want.

Keywords: Competition, markets, capital financing, managed care, health care reform.

an markets give us the kind of health care system we want? This question, posed by Tom Rice (1998a) and many others, may provoke both visceral reactions from some of this journal’s readers and methodological objections from others. I am among those who have argued that to classify policy choices as “market” versus “government” or “competitive” versus “regulatory” is likely to confuse an analysis of alternatives. In the case of cost control, these and other common labels, such as “managed care,” deflect attention from how and why policies actually work (Hacker and Marmor 1999; White 1999).

Yet the question is unavoidable because the broad ideological battle over the role of markets remains a basic dividing line and dominant theme in American health policy (for examples, see Bodenheimer 2005; Cogan, Hubbard, and Kessler 2005). In nearly all its efforts, the Bush administration appears to be guided by a belief in markets and private business, whether through “modernizing” Medicare into a system of competing private plans or replacing private insurance with Health Savings Accounts. In his third debate with Senator John Kerry (D-MA) before the 2004 presidential election, President George W. Bush revealed his views when he declared that “costs are on the rise because the consumers are not involved in the decision-making process. Most health care costs are covered by third parties. And therefore the actual user of health care is not the purchaser of health care” (Commission on Presidential Debates 2004).

Broad ideological judgments are powerful because people generally can more easily judge whether a policy is “the kind of thing we do” or “the kind of thing that I think works” than they can assess its substantive details. Hence, even though contrasts between “competition” and “regulation” or “market” and “government” frequently say little about substance, they can be expected to greatly influence policy debate in the future. Precisely because these beliefs are deeply entrenched, they are not easily changed by evidence (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1999). But the importance of these beliefs means that the long-term processes by which they change have a great influence on policy in any field (Mayhew 2001; Pierson 2001). This is why we should review the evidence about how market mechanisms work in medical care, even though classifying policy instruments as being more or less market oriented can be misleading and opinions can be changed only slowly by means of evidence.

Since the early 1990s, the U.S. markets for both medical services and health insurance have undergone a period of unprecedented dynamism as the traditional subservience of insurance companies to provider interests has finally been eliminated. Paul Starr’s (1982) “coming of the corporation” was real, if perhaps a bit delayed, and with the corporation came the pursuit of market logic above all. These events provide an opportunity to view market forces in action, and the health policy community has responded with extensive documentation and analysis, especially but not solely through the Center for Studying Health System Change. This work and especially the center’s Community Tracking Studies in twelve metropolitan areas document changes in organization, results, and thinking of participants in the medical care world.1 My article, therefore, is largely (though not exclusively) an interpretation of other scholars’ evidence. Because beliefs about markets carry so much ideological baggage, it is important to show that the judgments about detail and patterns from which I build my argument are not exclusively my own, but instead are statements by analysts who may have very different political views. Therefore I will quote rather more than the editors prefer.

What will happen to health care finance and delivery if the participants in these processes more closely resemble the players in a market than they did in the past for American medical care and at present for health care systems in other countries?

The evidence suggests that some of markets’ basic attributes— particularly how investors allocate capital—have been incompatible with the pursuit of a more equitable and efficient health care system. It also illustrates dynamics of market behavior, particularly herd behavior in response to compelling stories, which are not part of the standard economic explanations of how competition should work. For both these reasons, an interpretation of patterns in the United States since 1993 can shed new light on the prospect that markets could give us the kind of health care system we seem to want.

Methods and Plan of the Argument

“How markets work” and “how well markets work” are such general questions that they cannot be reduced to testable hypotheses. But they can be analyzed both logically and rigorously. In this article, I use the available mainstream evidence to make comparisons over time and between two forms of health care finance. The time series is mainly from 1993 through 2005, though I also look further back when that would be useful. National health expenditure and insurance access data provide macro trends, and the Health System Change studies and some others offer an extensive account of dynamics within the private insurance market. The two forms of insurance are the private, largely employment-based insurance that is available to most Americans under the age of sixty-five, and the Medicare program that is the main source of coverage for Americans who are aged sixty-five and older or are disabled. Medicare offers another perspective from both the outcome of attempts to include private plans within Medicare itself and a comparison of the costs and access for privately insured Americans to costs and access for Medicare beneficiaries. Accordingly, we can compare the performance of the market with the performance of an approach that weakly approximates the international standard (White 1995) for national health care/insurance systems. Medicare does not have the cost control potential of many national systems because it does not control system capacity and has not implemented hospital budgets. Yet it shares with other countries such attributes as compulsory contributions and membership, contributions related to ability to pay, cost controls applied across the universe of providers, a very wide risk pool for beneficiaries (one of the largest single pools in the world), and the resulting ability to be a price maker rather than a price taker, with only limited (but not insignificant) concerns that providers might exit the system.

Other scholars, from Kenneth Arrow to Mark Pauly to Tom Rice, have offered sophisticated discussions of how economic theory can be applied to medical care production and delivery (Arrow 1963, 2001; Evans 1998a, 1998b; Gaynor and

Vogt 1998; Glied 2001; Pauly 1998a, 1998b; Reinhardt 2001; Rice 1998a, 1998b, 2002; Rosenau 2003; Sloan 2001). By contrast, this article focuses on “the market” in its actual, not theoretical, form, as it existed in the United States during this period. The outcomes of interest are the cost of medical care, access to health insurance, and what might be called the rationalization of medical care. Rationalization here stands in for quality, which is very difficult to measure in even small batches, much less across the whole system.

By rationalization, I mean a reorganization of medical care so as to resemble more closely a standard of what Henry Aaron and William Schwartz call “medical efficiency:” “that every medical service offered produce larger expected benefits per dollar of total cost than any medical service not provided” (Aaron and Schwartz 2005, p. 96). The premise of what has often been called “managed care” is that in too many cases the wrong services are provided and that the right set of incentives or form of organization would lead to the right services provided to the right people at the right time. The theory of managed competition thus promised that a more market-oriented approach would increase value for money spent, by leading to better-informed or more prudent purchasing. As we will discuss later, advocates expected that the dynamics of market competition would yield a reorganization of health services in which more efficient and integrated systems, epitomized by the group-/staff-model HMO, would come to dominate the system (Gitterman et al. 2003). Because this was a prominent goal for market-oriented reformers during the 1990s, whether the market can be expected to deliver such a result (or, alternatively, why it cannot) should be a subject for evaluation.

Part 1 of this article sets the stage by outlining the basic attributes of the market in American medical care and ends with a discussion of the relationship between markets and the rationalization desired by many advocates. Part 2 reviews the basic data on trends in costs, access, and the organization of medical care from 1993 through 2005. I begin with 1993 both because this was the time of the most concentrated political action to change the system and because it is the most obvious breaking point in the data, seeming to show the beginning of a period of successful market-based change. I chose 2005 as the end point both because it is recent and because the implementation of the Medicare drug benefit (and its attendant subsidies to private insurers) must change the meaning of comparisons between Medicare and the private sector.

Part 3 uses the Health System Change and other analyses to explore the market dynamics that explain the trends regarding cost, access, and organization.

Part 4 addresses the idea that the markets’ failure to solve health care problems was a political failure rather than a market failure, in other words, that a political “managed care backlash” undid a promising start to market-led reform. Neither the Health System Change data on plan and provider behavior nor other careful analyses support that theory.

In this article’s conclusion, I argue that in order for any kind of “market-oriented” reform of American health care to have significantly positive effects on cost, access, and quality, it would have to include such substantial restrictions on the normal ways of doing business in U.S. markets that it would be barely recognizable as “market oriented” in the American context. For example, it would have to greatly restrict the flow of capital and ban many forms of insurance contracts.

Part 1: Attributes of the Market

Arguments in favor of improving health care through more reliance on markets and competition tend to be slippery. The failure of any particular approach can be written off as not getting competition “right,” that is, a failure of execution rather than principle. “Despite widespread acceptance of the competitive market model in the U.S. health care system,” Bryan Dowd writes, “debate continues regarding the optimal form of competition and the patient-professional relationship” (Dowd 2005, p. 1501). In other words, no remotely optimal form has been identified in practice, but we can keep looking. In a fine review of recent developments, Paul Ginsburg (2005) explains many of the reasons why they did not lead to reliable cost control or improved access and quality. Yet he still suggests that perhaps some other kind of competitive approach might have better effects.

Although few hypotheticals can be dismissed entirely, some are quite improbable. The question for reform of American health care is not whether one can imagine virtuous competition in some theoretical world (although Rice 2002 and Rosenau 2003 give reason for doubt). Instead, the question is whether institutions of market competition in the current American political economy are likely to have virtuous results. “Markets” are not a form of organization that can be separated from the context of norms and other institutions. A “stock market,” for example, may be constructed in very different ways and for very different purposes in accordance with how politics, economic resources, and economic organization vary across countries (Lavelle 2004). The literature of political economy shows that the way capital is organized and the resulting corporate incentives and norms can differ across countries (as referenced in Arrow 2001; for more details, see Doremus et al. 1999; Shonfield 1965). The basic rules of national economic organization, such as wage and hours legislation, determine how both for-profit and not-for-profit firms can be managed.

At the most general level, a “market” can be defined as a network of buyers and sellers. According to this definition, a market day in classical Greece, the cloth industry of medieval northern Europe, the souk in Casablanca, and the American home-building industry all are the same phenomenon. Market exchange existed long before modern capitalism, but the ideology of markets and modern market institutions and the modern understanding of the concept are based on an economic system and its accompanying values that arose over the past two centuries (Barber 1995). Three aspects of modern markets are relevant to how behavior driven by “market incentives” and in a context of market institutions has affected and can affect the cost of, quality of, and distribution of access to American health care:

- Suppliers’ individual pursuit of profit (or income maximization). Note that this behavior exists in other systems as well. However, advocates of market incentives rely on this pursuit to create efficiency, so a system that gives greater scope to markets should impose fewer institutional constraints on income maximization and also create fewer social obstacles (such as norms of restraint) to that behavior. For example, the modern market differs from the medieval cloth trade because it lacks the norms and constraints associated with a guild system. Nonprofit organizations in a market system may pursue somewhat different values than do for-profit organizations, but their leaders still will be influenced by society’s approval of income maximization and by the market’s economic forces (Hall and Conover 2003; Rosenau 2003).

- Extensive shopping for care, whether by individuals or agents for individuals. In the United States, such agents could be employers, who are the main purchasers of insurance. Shopping in this case means choosing under some conditions of price constraint, not simply choosing which physician or hospital to go to without any price constraints (as can be done in Canada or Germany).

In theory, markets should maximize value because as suppliers pursue profit and invest in creating capacity in pursuit of profit, they will be disciplined by customers’ shopping. The need to offer

lower prices than the competition’s should encourage efficiency, and the drive to satisfy customers should encourage the creation of a diversity of products to match different individual utilities.

These first two factors are the “facets of competitive theory” that Rice identified (1998a, p. 29). But a third is equally important:

- Medical care providers and insurers that have extensive access to capital when the suppliers of capital (either equity or debt) are motivated mainly by the pursuit of profit: in other words, capitalism. It is possible to have “competitive” reforms that extract capital from the equation. For instance, the British National Health Service’s “internal market reforms” under Prime Ministers Margaret Thatcher and John Major sought to create a form of competition among hospitals but kept a tight rein on capital. The result was an extremely limited form of competition (White 1995), and none of the theories of “competitive” reform for the United States that I have seen contemplates anything like this.

Instead, as J.B. Silvers writes, the development of the U.S. health care system since Kenneth Arrow’s classic article on the welfare economics of health care in 1963 has included a massive growth in assets, “fueled by an unprecedented use of tax-exempt debt, retained earnings, and new stock” (Silvers 2001, p. 1019). Silvers then argues that relying on private capital has much the same effect whether the source is debt or stock and whether the recipient is a for-profit or a nonprofit organization. Nonprofit organizations that go into debt can go bankrupt or be forced into mergers, reorganizations, or changes in management. “With the use of other peoples’ money came the responsibility to meet more stringent financial requirements . . . the threat of bankruptcy is the ultimate lever of control and may be even stronger than the votes of shareholders” (Silvers 2001, pp. 1025-26). The marketization of the American health care system includes the subjection of even nonprofit providers to the “discipline” of the financial markets, in ways that are dramatically different from the world that Arrow described. For example, a world in which local institutions were managed mainly by local nonprofit boards was largely superseded because “competitive or financial threats have compelled a very large portion of all providers to merge with larger entities with resulting loss of local managerial control” (Silvers 2001, p. 1026). That is what a capitalist market looks like.

Markets and “Managed Care”

In the 1990s, the mainline theory of how markets would improve the American health care system relied on two factors: competition in some form and “managed care.” The course of events over the following decade reflected the realities of both markets and “managed care.” Before reviewing the events, therefore, we must make some distinctions about the latter.

As used in the health policy literature, the term managed care has two distinct meanings (for references to the use of the meanings and more extensive discussion, see White 1999). The first, closer to the commonplace understanding of “managed care,” assumes that somebody other than medical providers will in some way manage treatment decisions. We can call this managing treatments. Measures for influencing treatment decisions include third-party enforcement of standards (utilization review), providers’ responsibility for the costs of referrals or prescriptions (risk-bearing gatekeeping), and the creation of large delivery systems that may develop a practice culture of and internal management routines to enforce more conservative treatment (the traditional group/staff HMO). The second meaning of “managed care” in the literature, especially when applied to “managed care organizations,” is insurers’ contracts with some providers and not others. Hence what is being “managed” most directly is the network of providers that is offered to the insurer’s customers. This form of “managed care” can more accurately be termed selective contracting.

Selective contracting as such requires no management of treatments. Instead, it may be employed mainly by purchasers who hope to obtain lower prices by threatening to take their business elsewhere. Conversely, in principle, treatments could be managed without any selective contracting. For example, some national health care systems require or encourage access to specialists only through primary care gatekeepers. If selective contracting is essentially a way to lower prices, it will not involve the kind of system rationalization—the guarantee that patients receive the right care from the right provider at the right time—that was at the heart of the ambitions for competition-led reform.

Much of the rhetoric about the insurance transformations of the 1990s seemed to suggest a big shift to managing treatments. For instance, the “managed care backlash” was largely framed as objections to utilization reviews (“1-800-Mother May I”) or to gatekeeping.2 Analysts would speak of “Jekyll and Hyde” forms of managed care (Bodenheimer and Grumbach 2005, p. 45). But we will see that the managed care revolution consisted more of selective contracting than of managing treatments, which leads to two empirical questions. First, was the marketization associated with savings related more to discounting or to rationalization? Second, if the period of relatively good cost control was associated more closely with discounting, why wasn’t it stable, and why was the management of treatments less important than the common rhetoric (including both sides of the managed care backlash) suggested?

Part 2: Health Care and Insurance, 1993-2005

To the health policy world, the most obvious initiative in 1993 was President Bill Clinton’s ill-fated attempt to enact a national health insurance plan. At the time of this battle, costs were expected to quickly hit 14 percent of GDP and rise to 18 percent by the end of the decade (White 1995, pp. 239-40). Yet even when those projections were made in 1993, the cost trend in the private sector was dramatically slowing. This suggested to corporate managers that they could control their health insurance expenses without giving government the job.

Cost Control

A longer view, however, can show both why the cost restraint after 1992 seemed impressive at the time and why it was quite temporary. We first need baselines for how well costs can or should be controlled, for which both American history and the performance of other countries provide perspectives.

Figure 1 shows the basic trend in total health care spending as a share of GDP in the United States and nine other rich democracies. After growing much more quickly than costs in any of the other countries from 1980 to 1992, costs in the United States suddenly stabilized, so that cost control was equal to or better than that in other countries (except, interestingly, Canada) through the end of the decade.

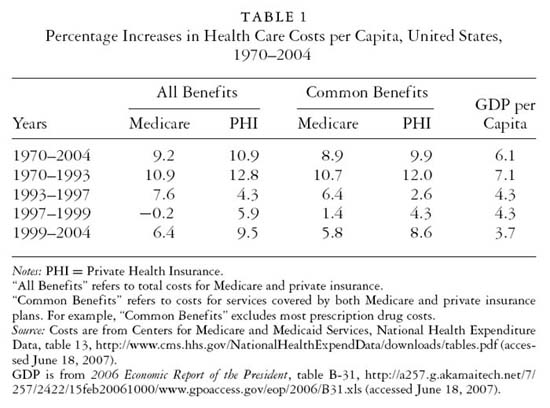

Table 1 provides a further comparison, between private insurance and Medicare. Private insurance’s benefit packages tend to be different from Medicare’s, in that they often are more generous, particularly regarding pharmaceutical benefits, but may offer less coverage of or need for benefits such as home health care. Therefore it is safest to compare all benefits and also those that the two systems share (such as physician and hospital services).

Table 1 shows that between 1993 and 1997 the spending trend for private health insurance slowed dramatically from the period before it and that spending increased much less quickly than for Medicare during the same years. This improvement was associated wi

th an accelerating shift by employers toward more “managed” health coverage, as well as by a political stalemate that prevented significant Medicare cost control legislation after 1990. As the economy also improved, both costs and premiums grew more slowly than the per capita GDP through 1997, so that national health expenditures declined as a share of the economy. Instead of rising toward 18 percent, they fell from 13.4 percent of GDP in 1993 to 13.2 percent in 1998 (Heffler et al. 2005, pp. W5-W75).

Around 1997, however, trends for both private insurance and Medicare reversed. The particularly rapid increase in pharmaceutical costs since the late 1990s perhaps might explain some of the worse performance of private insurance, although the table shows that different benefits explain only 0.3 percentage points of the 3.1 percentage point annual difference in cost trends between Medicare and private insurance from 1999 to 2004.

The reasons for changes in the private-sector trend are discussed at greater length later. Here we need to understand only what happened in Medicare. In 1997 the warring factions in the U.S. government finally compromised, in the Balanced Budget Act (BBA), on a set of savings measures for Medicare. Payment controls were strengthened where they had previously been applied (to inpatient care and physician services) and extended to areas that had been relatively uncontrolled (nursing homes, physical therapy, and home health care). In the language of political dispute, savings were derived from regulation, not competition (Moon, Gage, and Evans 1997; O’Sullivan et al. 1997).

In addition, the federal government initiated a crackdown on Medicare “fraud and abuse.” Legislation (such as BBA-97 and the Kassebaum-Kennedy insurance reform law in 1996), increased financing for investigation and prosecution (in both the FBI and the U.S. Attorneys’ Offices), use of laws with harsh civil penalties (the Federal False Claims Act), and particularly visible prosecutions of large providers (the University of Pennsylvania system and the giant Columbia/HCA for-profit hospital chain) appear to have scared the wits out of health care managers. Putting people in jail and levying multimillion-dollar fines on institutions are not cost control methods easily adopted by private payers. In response to the antifraud initiative, “DRG creep”—the phenomenon in which more and more admissions were classified as more complex and costly diagnoses under the prospective payment system for inpatient care—suddenly stopped in 1997 (U.S. CBO 1999). Home health care providers offering questionable services vanished from the world of Medicare contracting, and Medicare cost increases suddenly slowed. In fact, total Medicare costs even shrank slightly between federal fiscal years 1998 and 1999 (U.S. CBO 1999, 2001).

The new Medicare trend was almost as big a surprise as the earlier savings in the private sector and not much more sustainable. Providers screamed with the pain of cost constraint, and there was great political pressure for “givebacks.” Meanwhile, the federal budget had shifted into surplus so the government had money to give. Medicare’s costs thus returned to a pattern of rapid increase between 2001 and 2003, but the private sector’s costs rose even more quickly.

At the time, the fluctuating trends in the private sector appeared even more extreme than these data reveal. What employers (except for those who self-insure) and commentators see most directly are insurance premiums. Insurance premiums both fell more quickly and then rose more quickly than the underlying cost trends because insurance tends to follow an “underwriting cycle” in which periods of higher profits are followed by greater price competition among insurers (reducing the spread between premiums and medical costs). The cycle then turns, as higher “medical losses” lead to less price competition and a higher spread between premiums and costs.3 The data on premiums paid by large insurers show that premiums grew more quickly than costs from 1990 through 1995, more slowly from 1995 through 2000, and then much more quickly from 2001 to 2003. Through 2005, they continued to increase a bit faster than costs.4 This underwriting pattern matters, as we will see, because it includes herd behavior by insurers in both restraining premiums and then aggressively raising them.

By 2003, the political retreat from Medicare cost control, the collapse of cost controls in the private sector, and health insurers’ pricing strategies combined to return the American health care system to the cost crisis in which it had been in 1993, even though Republican control of the federal government kept national health insurance far away from the political agenda. As a share of the economy, national health expenditures rose from 13.2 percent in 1998 to 16 percent in 2004. In early 2006 they were projected to rise to 20 percent of GDP by 2015 (Borger et al. 2006).

As table 1 shows, from 1970 to 2004, costs rose a bit more rapidly for private insurance than for Medicare. From 1993 to 2004, the gap for “all benefits” was almost as large as before, although the gap for “common benefits” narrowed substantially. Except for the brief period from 1993 to 1997, “the market” has not been able to control costs as well as Medicare has. In addition, Medicare beneficiaries appear to be, on average, “generally more satisfied with their health care than are privately insured people under age sixty-five” (Boccuti and Moon 2003a, p. 235).5

Coverage

The cost slowdown of the mid-1990s had a positive effect on access to private health coverage. The combination of rapid economic growth and significant cost control made health benefits more affordable for employers and therefore restrained the growth in the share of costs that employees would have to pay to cover their families. As a result, employment-based coverage reversed its decline and, between 1994 and 2000, rose from covering 64.4 percent of the population to covering 66.8 percent. Meanwhile, coverage for the needy through the Medicaid program declined from 12.7 percent of the population in 1994 to 10.5 percent in 1999, because of both the good economy (which reduced need) and the “welfare reform” that reduced participation in Medicaid. These trends, however, then reversed. By 2003 only 63 percent of Americans had health benefits through employment—a smaller percentage than in 1994. Meanwhile, governments in the late 1990s responded to favorable budget conditions by expanding Medicaid eligibility. When the economy then turned sour, Medicaid enrollments grew to 12.8 percent of the population by 2003—higher than in 1994 (Fronstin 2004, p. 5).

By March 2003, nearly 45 million Americans—about 17.7 percent of the population below the age of sixty-five (and thus ineligible for Medicare) had no health insurance. Holahan and Wang summarized the pattern: “The extent to which the loss of employer coverage resulted in people becoming uninsured depended on their access to public programs” (2004, p. W4-31).

Cost matters to access: when both governments and employers were doing well financially, they tended to maintain or expand coverage, and when they were not doing well, they reduced or, at best, maintained the same coverage. But the overall pattern suggests that government was a bit more likely to intentionally expand coverage in good times and to resist contracting coverage in bad times. The decrease in Medicaid enrollment in the mid-1990s did result in part from welfare refor

m. This reform was not driven by budget concerns, however, but by conservative ideology and general public disgust with the previous system. In addition, as written, the 1996 law was supposed to maintain the entitlement to Medicaid benefits. Much of the decline was viewed as a failure of state administration, and in the late 1990s, the states actually made efforts to rectify those failures of outreach. Medicaid turned out to have enough “support among coalitions of public officials, health care providers, and local advocates” to “protect the program in hard times and enlarge it when the clouds lift” (Hoadley, Cunningham, and McHugh 2004, pp. 143-44). It should be no surprise that private market dynamics are not as reliable a way to subsidize poor people as government is, even in the United States. Indeed, equity is not what markets are supposed to provide (Pauly 1998a).

Cost controls are good for payers and bad for providers. For example, the period of strong cost controls had particularly negative effects on major teaching hospitals. Not only were they (for a while) at some disadvantage in contracting with private insurers, but they were hit by the antifraud campaign in Medicare, and many of them made unsuccessful investments (such as purchasing physician practices) during the 1990s. MedPAC estimates that in 1999 at the peak of the effects of the Medicare restraint, the average operating margin for teaching hospitals had fallen to 0.2 percent, which means that many of them were in the red (MedPAC 2001, pp. 69-71).

Public policies did, however, ameliorate the effects on access. Safety-net hospitals benefited from the Medicare and especially Medicaid “Disproportionate Share Hospital” (DSH) programs (Zuckerman et al. 2001). Academic medical centers also received payments for medical education and benefited from the boom in National Institutes of Health funding at the turn of the century. Reduced income from the spread of “managed care” was associated with physicians providing less charity care (HSChange 1999). Shrinking inpatient capacity (in almost all markets) and facility closures (in many) did cause many problems with access to emergency departments; ambulances shunted from one emergency department to another became common by 2001. Yet these pressures were somewhat ameliorated by a mix of measures, including the expansion of community health centers, the reorganization of dispatching systems for ambulance services, and hospital managers’ choosing to expand emergency departments in hopes of catching more inpatients (Brewster and Felland 2004; Felland, Felt-Lisk, and McHugh 2004; Kellerman 2004; Melnick et al. 2004).

The basic pattern, then, was that the market did threaten the “safety net” but that the safety net was protected—mostly—by political decisions. By 2003 a larger proportion of Americans was uninsured than in 1993, and more Americans were dependent on government “safety-net” programs such as Medicaid and subsidies to community health centers and academic medical centers.

The Failure of Rationalization

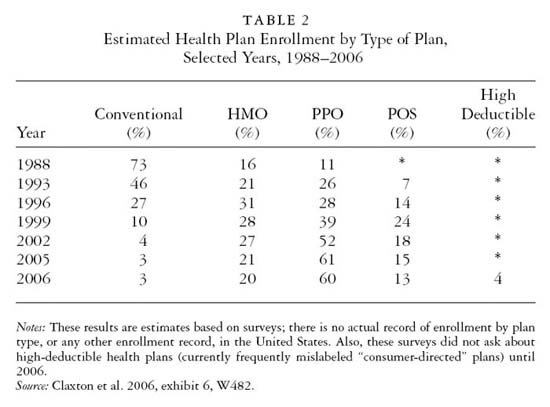

The period of cost control within the private insurance system was part of a longer period of system transformation. Over a bit more than a decade, conventional indemnity coverage nearly disappeared from the private benefits arena. According to table 2, survey responses in 1988 indicated that nearly three-quarters of covered beneficiaries were in conventional plans, and by 2006 the surveys showed conventional plan enrollment at 3 percent of the workforce, less even than in the new “high-deductible” plans.

This transformation definitely did not lead to the kind of rationalization desired by so many health policy analysts. From 1988 to 1996, as 46 percent of enrollees shifted from conventional to other plans, about a third moved into HMOs, raising the HMO total to 31 percent. Enrollment in PPOs grew even more quickly, and a third form, the point of service (POS) plans, also took up almost a third of the exodus from conventional insurance.

Moreover, the growth in HMOs after 1992 consisted entirely of increases in varieties other than the group or staff models of prepaid group practice (Gray 2006, p. 313). During the 1980s, other types of plans had proliferated, including independent practice associations (IPAs), networks, and mixed forms. The key point is that all these plans resembled insurance carriers more than integrated group practices (Gray 2006, p. 314).

As Gitterman and colleagues write, “Policy reformers who extolled the benefits of health maintenance organizations (HMOs) in the late 1970s and early 1980s emphasized in particular the cost and quality advantages of PGPs vis-Ã -vis solo and single-specialty fee-for-service (FFS) providers” (2003, p. 567). The model was Kaiser, which, for reasons discussed later, did not work well in the marketplace. Kaiser’s own tribulations were symptomatic: through acquisitions, it managed to expand successfully into Washington, D.C., in 1980 and the Atlanta area in 1990, but its expansions into Texas, Kansas City, New York, New England, and North Carolina failed (Gitterman et al. 2003, p. 590).

Because they did not simply accept the prices that caregivers wished to charge, and also used some modest methods of utilization management, the newer HMO forms had advantages over conventional indemnity insurance. Modest cost control is better than no cost control. Nonetheless, these new HMOs more closely resembled PPOs than traditional HMOs. Table 2 shows the market share of HMOs declining in 1999 compared with 1996.6 In one estimate, by 2002, 112 million Americans were enrolled in PPOs, more than twice the number in HMOs (Hurley, Strunk, and White 2004).7 By 2005, 61 percent of individuals enrolled in private plans were in a PPO system. In 2004, only twelve versions of the ideal HMO remained, serving 7.6 million enrollees. A decade earlier, there had been ninety-eight, serving 11.8 million enrollees (Schoenbaum 2004). Thus, by 2004, John Iglehart, the founding editor of Health Affairs, could conclude that

Lingering visions of the ideal health maintenance organization (HMO) still color policymakers’ perceptions about the less organized provinces of the health system. It is still fashionable to argue that the object of policy should be to nurture competition for consumers’ allegiance between high-performance health plans. In fact, though, relatively few such plans exist. Evidently, a rare and fortuitous combination of circumstances is needed to incubate the kind of large multispecialty groups on which true HMOs are built. (2004b, p. 35)

These circumstances had allowed the development of Kaiser Permanente in certain markets and at certain times. Kaiser still was seen as a model of rational service delivery (Weiner 2004). But this model has large management costs and requires far more capital investment to create and so provides a lower return on investment than do other approaches. These disadvantages were evident in the early 1990s (White 1995, pp. 184- 85) and from the rise of other forms of HMO in the 1980s (Gray 2006), and the developments from 1993 to 2005 confirm those effects.

If the savings in the mid-1990s did not come from what Iglehart called the “ideal health maintenance organization,” what was their source? HMOs of all sorts used measures that reduced the number of hospitalizations, and other physicians and

insurers copied that behavior. Most of the savings, however, appear to have come from threatening not to contract with providers, which for a while allowed plans to win better prices.

The most obvious evidence that the management of treatments was not the primary cause of savings is that the growth of premiums slowed for all types of health insurance, from HMOs to conventional indemnity plans (HSChange 1997a). At the same time, government reviews showed declines in the prices paid by private insurers (PPRC 1996, p. 216; ProPAC 1997, pp. 22-25). The preeminence of prices is often revealed indirectly in commentaries from that time. As one 1997 report explained:

Health plans, in early attempts at cost control, used fairly crude measures, including leveraging aggregated purchasing power to negotiate price discounts with providers. They turned their attention next to the potential for shifting service delivery from inpatient to outpatient settings. Concurrently, they pursued strategies for reducing service demand. “Now we’re at the stage where cost savings ultimately will come from managing care better,” one analyst contended. (HSChange 1997b, p. 2)

In other words, they weren’t quite “managing care” yet. Selective contracting was more important than the management of treatments.

Unfortunately for those who paid for medical care (but not for those who sold it), the ability to save by demanding discounted fees was only temporary. Part 3 explains how plans gained and then lost market power, and provides more evidence of the primacy of prices.

The transformations within the American health care system extended beyond the triumph of the PPO. Insurers and hospital systems also consolidated, and innovation took unexpected forms.

There were half as many health plans in 2004 as in 1996 (HSChange 2004). The Blue Cross and Blue Shield systems used their advantages in contracting (market power as the biggest customer) to grow from 65 million covered lives in 1994 to 91 million in 2004 (Iglehart 2004a). In thirty-eight states the largest firm controlled at least one-third of the insurance market; in sixteen states it controlled at least half; and everywhere except California and Nevada it was a Blue plan. Much of the remaining private enrollment was in the hands of Aetna, UnitedHealth Group, or CIGNA (Robinson 2004a). Blue Cross plans consolidated further through mergers, in some cases also converting to for-profit corporations (Grossman and Ginsburg 2004b).

The data on consolidation among hospitals are less systematic. In particular, we have more information about mergers than acquisitions and not much information about hospitals’ vertical integration or the extent to which hospitals bought physician practices, nursing homes, and other pre- or posthospitalization services (Cuellar and Gertler 2003). Nevertheless, starting in about 1993, hospitals “consolidated at an unprecedented rate” (Capps and Dranove 2004, p. 175; see also Spetz, Mitchell, and Seago 2000). Hospital managers were particularly active consolidators from 1995 to 1998. In 1995 about one-third of admissions were to hospitals with at least one local hospital partner; by 2000 that figure had risen to nearly half (Cuellar and Gertler 2003, p. 80). Hospital managers consolidated systems in order to strengthen their bargaining power with insurers, and studies show that consolidation did indeed enable hospitals to extract higher-than-average price increases (Capps and Dranove 2004; Cuellar and Gertler 2005).

The period of the fastest consolidation nevertheless included some horrendous failures. The most spectacular was the collapse of the Allegheny Health, Education and Research Foundation (AHERF), which had evolved from the Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh to a statewide system in Pennsylvania (Burns et al. 2000). “AHERF,” the authors report, “erroneously assumed that economies of scale and other efficiencies would flow automatically from its system-building efforts” (Burns et al. 2000, p. 33). Following closely behind was the development of Physician Practice Management (PPM) companies, a whole industry that rose and collapsed in about five years. As Uwe Reinhardt explained, stock market analysts first “hailed” the industry as “the capitalist salvation of a moribund cottage industry [physicians] starved for financial capital and managerial expertise” (Reinhardt 2000, p. 44). Firms increased total earnings and earnings per share by acquiring other firms; because market participants looked at earnings growth rather than profitability, they bid up share prices, which in turn allowed PPM companies to use overvalued shares to finance the purchases directly or justify borrowing. Unfortunately, however, the acquiring firms eventually had to stop acquiring (so their earnings stopped growing so their stock price would fall); or to pay for the debt they used to acquire other firms (with money they did not have); or to discover that combining firms made the larger enterprise, if anything, less efficient, through clashes in corporate culture, incompatible information systems, or demoralized employees (Reinhardt 2000, pp. 47-49). In the end, the “rapid . . . rise and fall” of the PPM industry “was driven mainly by pyramidlike funny-money games” (Reinhardt 2000, p. 50).

More recent developments make more economic sense but still reflect a churning and system restructuring that bears little relationship to theories of how the market would integrate care. In particular, rather than the system’s developing to favor primary care providers and integrated group practice, the system has returned to dominance by specialists.

According to the dominant story of the early 1990s, “the perceptions [my emphasis] that tightly managed care would become the dominant model in the United States and that there was a surplus of specialists placed [primary care providers] in a critical position” (Casalino, Pham, and Bazzoli 2004, p. 82). By the late 1990s, however, specialists realized they had “incentives to form single-specialty groups both to gain negotiating leverage with health plans and to profit from imaging and surgical services without having to share governance and revenues with PCPs in a multi-specialty group” (Casalino, Pham, and Bazzoli 2004, p. 83). Larger specialty groups also were desirable to generate the capital needed to purchase imaging and other equipment. Hence participation in multispecialty groups began to weaken while single-specialty groups became more popular. “Fear of managed care is what drove us together,” one medical director said, and “success in contracting is what held us together” (Casalino, Pham, and Bazzoli 2004, p. 86).

In some markets, specialty physicians consolidated and organized to a point that they could consider challenging hospitals. Largely because of favorable payment rates from both Medicare and private insurers, cardiac care and some other services (e.g., orthopedic surgery) are profit centers for hospitals. In a general hospital or academic medical center, these services cross-subsidize money-losing services. If they could be carved out separately as specialized surgical hospitals, however, those extra profits could be shared between the entrepreneurs who created the specialty hospitals and the physicians who provided the services. Whereas hospital managers had an incentive to try to grab business from other hospitals (by developing nicer facilities, attracting specialty physicians, etc.), the specialists might try to free themselves from the hospitals and control their own facilities.

By 2002, physicians and for-profit specialty hospital companies had created forty-eight small hospitals with substantial physician ownership. In the twelve markets covered by the Center for Studying Health System Change’s community tracking study, eleven new specialty hospitals were built b

etween 1997 and 2002. Much of this development occurred where the state regulatory environment was permissive, that is, in states with no certificate-of-need (CON) programs (Hackbarth 2005). In one Indianapolis example, specialty groups associated with one system “initiated discussions about building a heart hospital with MedCath, a national for-profit cardiovascular service company.” This threat forced the hospital to agree to build its own new facility, “with the physicians owning up to a 30 percent share through a joint venture arrangement” (Devers, Brewster, and Ginsburg 2003, p. 2).

Advocates naturally claimed that specialty hospitals were growing because they offered real operational advantages. For example, surgeons could schedule their use of the operating room without worrying about being interrupted by emergencies, because there was no emergency department. But there was good reason to suspect that physicians with ownership interests in an institution might refer their more profitable patients there and send the others to the full-service hospital. Indeed, the margin of profit in specialty hospitals was significantly higher than that in community hospitals (Devers, Brewster, and Ginsburg 2003; Hackbarth 2005). In response to these concerns, as part of the 2003 Medicare legislation, Congress and President Bush agreed to place a moratorium on Medicare’s contracting with new specialty hospitals owned by physicians, and MedPAC advised that the moratorium be continued through 2006 (Hackbarth 2005).

Overall, a period of market-led transformation of American medical care resulted in the consolidation of both insurers and hospital systems; a strengthened role for specialists, in the form of multispecialty groups; a great deal of wasteful investment in organizations that later went bankrupt; and the eclipse of the organizational form, the integrated prepaid group practice, that theorists of managed competition believed the market would favor. Nor did this transformation control costs or expand access. Why were these the results?

Part 3: Dynamics of the Health Care Market

The ups and downs in the privately funded side of America’s medical care were caused by how pursuit of self-interest within a market context was shaped by both the beliefs of the market participants and the underlying factors of supply and demand.

Further Attributes of the Health Care Market in the United States

In part 1, I argued that the basic aspects of a modern market include suppliers that are relatively free to seek to maximize income, purchasers (employers in particular) that shop extensively for value, and capital that flows freely to wherever the people who control the capital think it would be most profitable. Suppliers and providers are broadly free to contract with each other. The United States’ medical and insurance markets also have the following characteristics:

Unequal Market Power. Different participants in a market relationship have different amounts of power. Power in a market is basically the ability to walk away from a contract if one does not get a price one likes—or to force others to agree to a contract on terms that one does like. As we will see, market power has both a hard component, such as size and number of competitors, and a soft component, the expectations and attitudes brought into bargaining situations. Paul Ginsburg described a similar concept, arguing that the type of organization with the power to lead differed across markets. Thus hospital systems had the power to lead in Portland, Oregon, whereas physician groups were the leaders in Orange County, California, and health plans led (at that time) in Minneapolis-St. Paul. He argued as well that the power to lead was associated with strong management and access to capital (Ginsburg 1997, p. 366).

Contracting in Multiple Directions. American health care markets are not simple structures in which one set of buyers meets one set of sellers for one set of products. Instead, markets have multiple levels, for instance, health care providers selling to insurers who then sell to employers. Thus some participants contract in multiple directions, and that fact shapes both market power and strategies.

Herd Behavior. Markets are arenas for herd behavior, in which participants are told, and come to believe, a particular story and act as if that story were true. As we will see, such herd behavior can represent a self-fulfilling prophecy—up to a point. Then the herd may stampede in a different direction. The point here is that herd behavior is simply part of the broader political economy. Just as the flow of funds created a boom-and-bust cycle in telecommunications stocks or in the NASDAQ overall, and the “smart money” sometimes rewards mergers and, at other times, rewards firms that concentrate on “core competencies,” the flow of capital to or away from health care organizations has been, and will be, driven by moods and stories, such as the boom and bust in the Physician Practice Management business (Reinhardt 2000).

Prices, Institution Building, and the Triumph of the PPO

What happened to prices is a story of market power. During much of the 1990s, market power was the holy grail for participants in various medical businesses. Beliefs about market power especially encouraged managers of both insurance companies and medical enterprises to seek greater scale. The Aetna and U.S. Healthcare insurance companies, for example, gained market share quickly, merged in 1996, and grew to cover 21 million lives. As Jamie Robinson explained, Aetna

sought to move as much enrollment as possible into the fully insured HMO, counting on aggressive provider discounts to control medical costs. . . . The Aetna U.S. Healthcare managed care strategy relied above all else on massive scale, on millions in enrollment and billions in revenue to pressure physicians and hospitals to participate at low payment rates; cover the administrative overhead of utilization management; dilute adverse selection from weak underwriting; and spur continuous rounds of lower costs, lower premiums, and further growth. (Robinson 2004b, p. 45)

The expectation, however, turned out to be inaccurate. Aetna lost large amounts of money; the top management team was dumped; and the company survived only by entirely reconfiguring its business. By 2003 Aetna had only 13 million enrollees and only 3.3 million in its HMO lines.

Aetna’s strategy failed because providers revolted, “consolidating their local markets and demanding rate increases, litigating over delays in payment and denials in authorization, and, in some instances, simply walking away from HMO networks” (Robinson 2004b, p. 45). In other words, “managed care” in this case mostly meant the use of selective contracting to drive down prices, and it failed when the providers developed sufficient market power to resist.

Robinson’s and Casalino’s accounts of what happened in the peculiar case of California tell a parallel story. California was different because of the massive presence of Kaiser Permanente, the prototypical group- /staff-model HMO, which really did “manage care” (treatments) through a distinct practice culture and internal controls. Inspired by or fearful of that example, in many parts of the state during the 1980s and 1990s, physicians formed large multispecialty groups (similar to the Permanente group of Kaiser) and contracted with a variety of HMOs to take on risk through capitated payment for patients. Following Kaiser’s lead, these groups saved money by “reducing the numbers of admissions, decreasing lengths-of-stay, and reducing payment rates to hospitals” (Casalino 2001, p. 99). They thought they would find greater savings and so chose to ta

ke on as much risk as possible through capitation for a wide range of services. And they did do more management than medical groups in other states (Robinson 2001).

By the late 1990s, 16 million people were in HMOs in California, receiving care through 250 medical groups. Then, as Robinson explains, “came the crash” (Robinson 2001, p. 82). In the rush for market share, physician groups (just like Aetna) accepted prices that turned out to be lower than their costs. Robinson explains that “medical groups accepted low rates because they wanted to attract patients from competing organizations.” As with Aetna, however, the California medical groups could not control costs outside their organizations very well, and as a result the low rates wreaked havoc on their internal finances. The basic problem for medical groups was market power, or its absence. “The limits of leverage against health plans stem from the simple fact that health care is local, and even the largest medical groups never built anything approaching monopoly power in any particular submarket” (Robinson 2001, p. 91).

But why did physician groups (and Aetna and everybody else) have to compete by price discounting rather than by managing care to make it more appropriate? The California experience makes clear that even if it were true that an information base for efficiently managing care existed and could be made convincing to physicians, managing treatments would still require building and managing complex organizations. Markets neither create the necessary information nor create complex organizations, and both turn out to be extremely difficult.

The theory was that capitation would give medical providers incentives to provide “the right care, at the right time, in the right place, with the right use of resources” (Casalino 2001, p. 99). That seemed to call for growing quickly, both to obtain contracts and to build service capacity. “The race to become large enough so that the other side must contract with you,” Casalino reported, then “resulted in organizations growing at rates that HMO and group leaders acknowledge have sometimes been unmanageable and to sizes that many believe may be larger than is warranted by economies of scale” (2001, p. 103). Consolidation also had negative effects on culture and work incentives, because it, in Robinson’s words, brought together “physicians who did not know or appreciate each other, who shared no common vision or culture, and who treated fewer patients per day than when self-employed” (2001, p. 89). Moreover, there were diseconomies of scope. Although multispecialty groups were seen as a means to coordinate all forms and levels of care, as Robinson explained, “amalgamation also can transfer inside the organization the diversity and disunity formerly coexisting under the principle that good fences make good neighbors.” This resulted in fights over internal divisions of resources, with specialists threatening to withdraw en masse in order to “extort greater shares of the overall budget” (Robinson 2001, p. 92).

In theory, groups might have competed by providing higher quality through more appropriate management of treatments. Yet this was not practical because when groups are paid by capitation and so bear risk but nobody has devised a plausible risk-adjustment mechanism, the threat of adverse selection means there is no business case for quality. As Casalino notes, “We do not see billboards advertising that HMO A or Medical Group B provides outstanding care of diabetic patients . . . capitated organizations with a reputation for high quality may suffer a double financial hit: a loss on their investment in quality, and a loss from attracting sicker-than-average patients.” Therefore groups that had instituted quality improvement programs such as disease management concluded that they were not good for the bottom line and scaled them back (Casalino 2001, pp. 104-5). The dynamic of competition meant that even if preventive or wellness measures had improved the performance of the system as a whole, the fact that the provider of those services could not be sure of reaping the financial rewards made their provision economically irrational.

The competitive failure of the group-/staff-model HMOs and of the California group practices was another face of the PPOs’ triumph. There are three main reasons why PPOs triumphed in the marketplace. First, more tightly managed care is less than popular with patients. HMO became an unpopular term during the 1990s. While the “managed care backlash” produced only small (though frequent) legislative victories (see part 4), employers appear to have decided that their employees wanted fewer restrictions. But employers might not have done so if the HMO products had had what employers and employees considered sufficient price advantages. Instead, the PPO cost containment disadvantage from interfering less in patient care was at least partly offset by the fact that interference also requires extra expense. Accordingly, by the early 2000s, there was little difference in the cost of coverage through HMOs and PPOs (Hurley, Strunk, and White 2004; Schoenbaum 2004). This similarity of cost may have reflected a similarity in substance, as at that point HMOs overwhelmingly consisted of IPAs and other less tightly managed models.

From a policy perspective, the PPO form has disadvantages that become evident from comparisons with traditional Medicare. Analysts at the Center for Studying Health System Change thus found “puzzling” both the rise of PPOs and their advancement as a proposal for Medicare reform. After the 2003 “Medicare Modernization Act” proposed expanding the PPOs’ role in Medicare, these analysts commented,

Almost certainly, PPOs cannot get sustainable discounts from physicians or hospitals that approximate rates paid by Medicare, as even the tightest HMO networks rarely approach Medicare’s administered prices. In that respect, Medicare is the “mother of all PPOs” because it enjoys superior discounts over virtually all private payers. That the PPO will not be able to achieve the low administrative costs of traditional Medicare is a point conceded even by proponents of PPOs.

PPOs might look good in the market compared with HMOs, they added, but “the PPO arrangement enjoys none of these advantages relative to traditional Medicare” (Hurley, Strunk, and White 2004, p. 67).

In the market, however, PPOs were competing not with Medicare but with other private insurance plans. This context revealed the most important advantage of PPOs: the flexibility of the product. Insurers can create basic networks and then customize the offerings to different employers’ preferences for passing on the costs to employees (through cost sharing) or fitting a network to where their employees live. The traditional group- or staff-model HMOs were at a special disadvantage on these dimensions, as they had avoided cost sharing and could not customize networks because they were built around large clinics. In contrast, an insurer could rent its PPO network to an employer that chose to self-insure—and lots of employers did so, in part because of regulatory requirements for health insurance (Hurley, Strunk, and White 2004).

PPOs therefore have a major a

dvantage in one of the aspects of competition that economists emphasize: customizing products to appeal to purchasers with different “tastes” (Glied 2005; Pauly 1998a). In the standard economic argument, choice improves personal utility (each purchaser receives a preferred product) as well as the total social utility. This argument applies to the choices actually offered in the market but not to all possible choices. Therefore it says nothing, for example, about whether PPOs could compete successfully with traditional Medicare if employers were offered that option (White 2007). Purchasers of insurance had to deal with what the market actually offered. In that situation, with employers being the true purchasers, the plans that did best in the competition were those that were “diversified into multiple networks, benefit products, distribution channels, and geographic regions” (Robinson 1999, p. 8). The flexibility of the PPO product allowed insurers to offer a different “plan” to each customer (as either insurance or a network rented by a self-insured employer).8

As the costs and access figures show, the advantages of PPOs in the American marketplace do not remotely suggest that the marketplace was working well. But they also do not quite explain how the market did work.

Stories, Behavior, and Entrepreneurship

The most striking aspect of the accounts of market behavior in health care in the 1990s is that activity appears to have been influenced by shared stories, which rose, fell, and were changed in the health policy and business communities.

The rush into HMOs (and PPOs) from 1993 through 1997 was triggered in part by the publicity about “managed competition” during the 1993/1994 debate about the Clinton health insurance proposals. Paul Ginsburg reports that “many persons interviewed” in the Community Snapshots Study (which involved fifteen communities) “mentioned the degree to which the Clinton administration’s proposals spurred organizations to initiate changes to prepare themselves for the potential world of managed competition” (Ginsburg 1996, p. 18). This market behavior involved group think among four sets of actors.

First, entrepreneurs and managers of insurance companies had to believe that this was how insurers should do business. Jamie Robinson’s account of Aetna’s tribulations neatly illustrates the alternation of belief and disillusion in that part of the system. Second, providers had to be willing to sign selective contracts with managed care organizations at discounted rates. In this sense, the move to selective contracting was a self-fulfilling prophecy: because they were told “managed care” was the wave of the future, providers figured they had to get ahead of the wave in order “to ensure they did not lose patients or revenue as beneficiaries moved into managed care” (Grossman, Strunk, and Hurley 2002, p. 3).9 Analyst Jeff Goldsmith referred to “panic-driven discounts” (HSChange 1997a, p. 4). These beliefs also were the reason why providers, seeking to protect themselves, merged or acquired networks horizontally and vertically (for an example of these calculations, and a rare exception, see Kastor 2004).

Employers had to believe these forms of insurance would save money. This belief depended less on prophecy than on desperation: something had to work better than what they had done before. When it actually did work better, for a while, employers pushed on, shopping for better deals as long as that worked.

Finally, investors had to believe that they would get high returns from providing the capital needed to build and expand these managed care networks. This also was a temporarily self-fulfilling prophecy. When the Center for Studying Health System Change convened a group of Wall Street analysts to discuss the health care market in 1997, the report noted that for-profit HMOs had been growing exceptionally fast owing to “access to capital; good balance sheets with large amounts of cash; highly valued stock that they can use as cash to make acquisitions and grow; highly sophisticated marketing and operating abilities; and innovative product development that responds to consumer interests and demands while controlling costs.” The problem with this view was that the part about controlling costs apparently was not entirely true, as shown by the observation that “despite the impressive growth of this small cadre of companies, much of this industry is not profitable now” (HSChange 1997b, p. 1).

Grossman and Ginsburg’s account of what happened in the insurance industry is very similar to Reinhardt’s account of how capital market enthusiasms allowed the boom-bust cycle for Physician Practice Management companies:

Some plans intentionally underpriced to gain market share. Plans believed they could price lower than their competitors without harming their bottom line because of expectations that larger market share, along with utilization management, would reduce costs. With the industry in its growth phase, publicly offered plans were valued based on a multiple of members and so had additional incentives to price to increase enrollment. The heavy capitalization of these plans provided a cushion for losses arising from such pricing. (Grossman and Ginsburg 2004a, p. 97)

Insurers were supported by investors who believed the story and so provided capital to pay for expansion. Then the believers in “managed care” encountered two problems with a good story.

First, too many people may believe the story. “As the industry peaked,” one participant in the center’s 1998 Wall Street roundtable commented, “everybody jumped into the business” (HSChange 1998b, p. 1). Second, the believers themselves may give the story too much credence. As employers switched plans for lower premiums, plan managers “appeared willing to sacrifice premium increases in exchange for entering new markets and growing their enrollments” (HSChange 1998a, p. 1). The crash came when a combination of provider disgust and desperation, provider consolidation (to increase market power), and provider exit changed their willingness to accept, and play their role in, the story.

By 2001, the center’s Wall Street analysts were agreeing that by consolidating, hospitals had gained dominant power in many areas. Where hospitals had not consolidated, insurers were propping up the weaker ones with better rates in order to prevent consolidation! Both plans and providers had abandoned the pursuit of market share and were concentrating on seeking higher prices so as to restore profitability, mainly because the “self-induced pain” of the era in which both sides believed in market share above all had been “phenomenal” (HSChange 2001, p. 3). Hospital managers also became more willing to risk confrontations. In a widely reported showdown in 2001, St. Joseph’s hospital system in Orange County, California, refused to contract with PacifiCare. It turned out that patients were more loyal to providers than to insurers: “St. Joseph was able to retain most, but not all, of its patients as they switched enrollment from PacifiCare to other health plans, which sent a powerful message to both sides about the consequence of contract showdowns” (HSChange 2003b, p. 3). Showdowns had similar results around the country because either enrollees who had a choice within their employer plans switched to follow their preferences or employers chose to accommodate their employees’ preferences.

By 2003, one participant in the center’s Wall Street to Washington gathering could say that “the last few years in the hospital industry are probably the best we’ve seen in 20 years.” Beds had been closed (through mergers, failures, etc.) to the point that the sellers had power over the buyers (HSChange 2003c, p. 2). My own community of

Cleveland is a good example: the large Mt. Sinai medical center closed and the Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals systems bought up much of the rest of hospital capacity, which left “no countervailing force . . . to check the systems’ power” (HSChange 2003a, p. 1).

As a result of these developments, a new story had come to dominate—and in essence coordinate—market behavior. Remembering the pain of the late 1990s, managers of health care providers and insurance companies were determined to keep prices up through “pricing discipline.” “I’ve never seen discipline in the industry from a pricing standpoint like I’ve seen now” (HSChange 2004, p. 2), said one insurance industry consultant, providing part of the answer to why the underwriting cycle had yet to turn back toward lower margins. After a period of contract showdowns between health plans and providers, conflict had declined largely because, in most markets, “plans have recognized and accepted their weaker position relative to providers” (White, Hurley, and Strunk 2004, p. 1).

One might wonder why consolidation among insurers did not allow them to resist the providers’ demand for increased payments. The simple answer is that there were two concentrated parts of the market and one fragmented part. The insurers had to choose between fighting a full-pitched battle with the providers or exploiting their own market power vis-Ã -vis the employers. Raising premiums to employers was a lot easier. In theory, employers could have demanded restrictive networks (at lower prices). But since everyone had agreed that employees did not like restrictive networks, and providers (especially hospitals) were not willing to discount much to get into such networks, there were not many available for purchase. Individual employers could not invent such a product; they could only shop around and find the relatively best deal by customizing other contract terms, such as cost sharing.

The system left substantial room for entrepreneurship, but this entrepreneurship did not serve to improve health care values. Aetna became profitable again in part because it rigorously improved its underwriting and shed its more expensive patients (Robinson 2004b). Some physicians pursued income more aggressively outside normal channels. In particular, they participated more heavily (for compensation) in clinical trials sponsored by drug companies and made more efforts to invest in specialty care facilities (Pham et al. 2004; for a very critical assessment, see Kassirer 2004).

Specialty physicians, as noted earlier, organized to create and exploit market power and, in some cases, tried to extract extra income from the hospital sector. Their ability to do so depended largely on the supply and demand aspects of market power. Thus, physicians were most likely to seek to create specialty hospitals where they had the “greatest leverage relative to plans because of a previous history of single-specialty consolidation (Indianapolis) or relative physician shortage (Phoenix).” They were least likely to do so where there were lots of physicians and the hospitals had overwhelming brand identity, as in Boston, or the specialists were disorganized, as in Miami (Pham et al. 2004, p. 75).

Such an exploitation of market power was possible, however, only because of the free flow of unregulated capital. In most countries, entrepreneurs would not be able to raise capital, build a facility, and expect the dominant public insurers or sickness funds to send their enrollees to the facility. Even in the United States, the normally weak certificate of need processes that still exist in some states appear to have restrained the development of specialty hospitals there.

The free flow of capital did not serve health care values such as cost control and access. Shopping involved mainly employers choosing among unsatisfactory alternatives—ever more expensive coverage with increasing cost sharing. Market power was used to exploit whoever was weakest. For a short while, that was providers, but it is now the purchasers. Behavior followed stories that in significant cases turned out to be untrue. The health care herd stampeded in one direction and then another.

The brief period of private-sector cost control was based mainly on dynamics of price negotiation that then reversed. The actual management of treatments was less important; the short answer why that was so is that negotiating prices is a lot easier than managing treatments. Although PPOs triumphed in the market, even as they did so, there was no reason to believe they could beat traditional Medicare in a fair competition. The market did not control costs, increase access, or help rationalize the American health care system.

Part 4: The Role of Political Backlash

The account here, though derived from mainstream analyses, is not quite the conventional wisdom. Instead, many readers may believe that the period of private-sector cost control was reversed by a politically driven “managed care backlash.” Where I emphasize how behavior in markets affected prices, the alternative argument would emphasize utilization controls. Where I emphasize employer and employee and provider pushback in contracting processes, the alternative argument would say that political pressures, such as legislation and regulation at the state level, caused insurers to retreat from tight utilization controls that had, for a short time, controlled spending.

A review of the literature on the political and legal dimensions of the backlash shows, however, that the market dynamics that I have emphasized, including a perception among insurers that their efforts to manage care were not cost-effective, were far more important than the limited regulation that occurred amid the rhetorical fury.

Utilization reductions were part of the reason that cost increases slowed in the mid-1990s. Group/staff HMOs certainly did reduce hospitalization rates (Dhanani et al. 2004). Moreover, health insurers did retreat from many of the methods of utilization controls that they had emphasized in the mid-1990s (Lesser, Ginsburg, and Devers 2003; Mays, Hurley, and Grossman 2003). We might expect that laws such as those inhibiting the “drive-through delivery” of babies contributed to this retreat from utilization controls (Liu, Dow, and Norton 2003; Morrissey and Ohsfeldt 2003/2004).

Most of the evidence clearly suggests, however, that legislation was a minor factor in both utilization and price developments. To be sure, the political process both fed off and added to the mood of public discontent, which may have encouraged plan managers to conclude that some forms of cost control were not worth the trouble. States passed a wide variety of legislation (for a summary, see Hall 2004). Yet there is very little evidence that legislation or regulations had important effects.

One indication of the low relative importance of legislation is the limited emphasis it receives in overview analyses. Whether intended or not, government does, as Lesser and colleagues report, play “a key role in shaping the structure and dynamics of the health care market, acting as both a purchaser and a regulator” (Lesser, Ginsburg, and Devers 2003, p. 340). Nonetheless, their account provides no instances of laws affecting behavior, even though it offers many examples of the influence of market dynamics. Mays and colleagues argue that government actions were one part of the overall environment of backlash. Again, though, their account emphasizes other factors. For example,

health plans cited several reasons for the movement to less restrictive provider networks: growing consumer demand for broad provider choice; the lack of reliable information for identifying efficient providers; difficulties in generating demonstrable cost savings from limited-network products; and the efforts of some hospitals and medical groups to become “indispensable” components of networks by consolidating

or building consumer loyalty. (Mays, Hurley, and Grossman 2003, p. 381)

Government regulation is conspicuously absent from this list. The authors report that plans in three of the twelve Community Tracking Study markets did claim that “state insurance regulations have steadily weakened the ability of gatekeeping and preauthorization requirements to constrain utilization” (2003, p. 385). Yet the retreat was evident in all twelve markets, and the plans allowing self-referral to specialists or eliminating some prior authorization requirements “uniformly cited consumer and provider dissatisfaction with administrative hassles as a primary motivation for scaling back their reliance on gatekeeping and preauthorization requirements.” Some plan respondents further explained that they were uncertain that the rules were effective in constraining utilization (2003, p. 384).

Studies that focused specifically on government action also found only weak effects, if any. Sloan, Ratliff, and Hall analyzed a wide range of “patient protection” laws, including laws that would have made managed care organizations liable for outcomes that could be blamed on their utilization constraints, a “prudent layperson” standard for determining when emergency services would be covered, direct patient access to ob/gyn physicians without referrals, minimum stay requirements for deliveries, and external review of coverage denials. They found very few effects on either the utilization of services or patients’ satisfaction with care. The only statistically significant effect on utilization was a greater use of emergency rooms after the prudent layperson standard was enacted (Sloan, Ratliff, and Hall 2005).