On February 10, 2021, less than one month removed from the final days of the Trump administration, the Lancet Commission on Public Policy and Health in the Trump Era published its report detailing the last four years of detrimental health policies, the last 40 years of corporate-friendly conservatism, and the last 400 years of structural racism and white supremacy.

The Commission was co-chaired by PNHP co-founders Drs. Steffie Woolhandler and David Himmelstein, and the full 33-member body included additional PNHP leaders, public health luminaries, and single-payer champions.

Full report:

https://www.thelancet.com…

Comment:

https://www.thelancet.com…

News release:

https://www.eurekalert.org…

Abstract

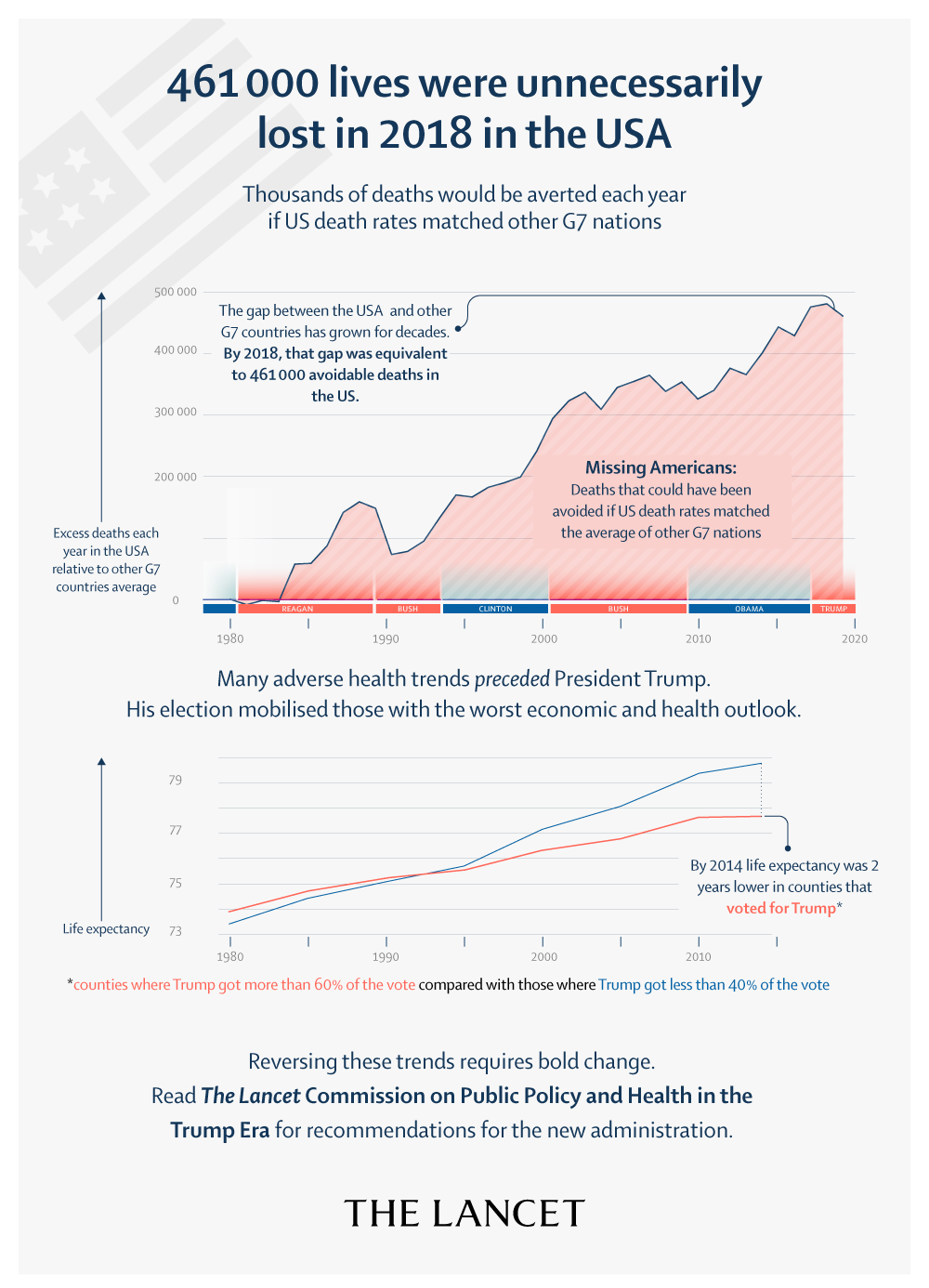

This report by the Lancet Commission on Public Policy and Health in the Trump Era assesses the repercussions of President Donald Trump’s health-related policies and examines the failures and social schisms that enabled his election. Trump exploited low and middle-income white people’s anger over their deteriorating life prospects to mobilise racial animus and xenophobia and enlist their support for policies that benefit high-income people and corporations and threaten health. His signature legislative achievement, a trillion-dollar tax cut for corporations and high-income individuals, opened a budget hole that he used to justify cutting food subsidies and health care. His appeals to racism, nativism, and religious bigotry have emboldened white nationalists and vigilantes, and encouraged police violence and, at the end of his term in office, insurrection. He chose judges for U.S. courts who are dismissive of affirmative action and reproductive, labour, civil, and voting rights; ordered the mass detention of immigrants in hazardous conditions; and promulgated regulations that reduce access to abortion and contraception in the USA and globally. Although his effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act failed, he weakened its coverage and increased the number of uninsured people by 2.3 million, even before the mass dislocation of the COVID-19 pandemic, and has accelerated the privatisation of government health programmes. Trump’s hostility to environmental regulations has already worsened pollution—resulting in more than 22,000 extra deaths in 2019 alone—hastened global warming, and despoiled national monuments and lands sacred to Native people. Disdain for science and cuts to global health programmes and public health agencies have impeded the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, causing tens of thousands of unnecessary deaths, and imperil advances against HIV and other diseases. And Trump’s bellicose trade, defence, and foreign policies have led to economic disruption and threaten an upswing in armed conflict.

Introductory online forum

Media coverage (print)

- “Trump’s Policy Failures Have Exacted a Heavy Toll on Public Health,” by Jacob Bor, David U. Himmelstein, and Steffie Woolhandler, Scientific American, March 5, 2021

- “Roughly 40% of the USA’s coronavirus deaths could have been prevented, new study says,” by Ken Alltucker, USA Today, Feb. 15, 2021

- “U.S. could have averted 40% of Covid deaths, says panel examining Trump’s policies,” by Amanda Holpuch, The Guardian, Feb. 11, 2021

- “4 out of 10 American deaths last year could have been avoided says a new analysis,” by Anagha Srikanth, The Hill, Feb. 11, 2021

- “Lancet commission examines Trump’s COVID response,” by Erin Schumaker, ABC News, Feb. 11, 2021

- “Death Toll Associated With Trump Administration Goes Beyond Covid-19, Says Lancet Report,” by Bruce Y. Lee, Forbes, Feb. 11, 2021

- “Damning analysis of Trump’s pandemic response suggested 40% of US COVID-19 deaths could have been avoided,” by John Haltiwanger and Aylin Woodward, Business Insider, Feb. 11, 2021

- “40% of US Covid Deaths Could Have Been Avoided: Report,” by Michael Rainey, Yahoo! Finance, Feb. 11, 2021

Media coverage (video/audio)

Interview with Dr. Mary Bassett, Democracy Now!, Feb. 15, 2021

Interview with Dr. Adam Gaffney, Cheddar News, Feb. 11, 2021

Interview with Dr. Steffie Woolhandler, Civic Rx, Feb. 19, 2021

Interview with Dr. Mary Bassett, In Conversation With…, Feb. 11, 2021