By Don McCanne, M.D.

“If the piece has a hero, it’s an unlikely one: Medicare, the government program that by law can pay hospitals only the approximate costs of care. It’s Medicare, not Obamacare, that is bending the curve in terms of cost and efficiency.”

– Richard Stengel, managing editor, TIME, regarding “Bitter Pill’ by Steven Brill (1)

Under President Barack Obama, the nation once again undertook the effort to reform health care so that everyone would have access to essential health care services. But this time it was different. The costs of health care had become unbearable to individuals, to employers, and to the government. It became an imperative to bend the cost curve of health care – to slow the growth in health care costs to a sustainable level.

Although the effort resulted in the enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Obamacare), the effort falls far short. Not only will 30 million people remain uninsured, underinsurance in the form of low actuarial value health plans will become the new standard. Although the legislation included many features designed to control health care costs, most are only tweaks and unfortunately will have very little impact when considering the enormity of the problem.

Perceiving that more measures are needed to control spending, President Obama and the members of Congress are considering significant changes to Medicare, as if the only health care cost problem were the projected increases in Medicare spending which the government faces. From a policy perspective, this would be a disastrous approach since the excess cost escalation is not occurring in Medicare, but rather it is occurring in the private sector – especially the health care that is funded through private health plans and through employer-sponsored self-insured plans. Our government stewards could not be further off target should they start to trim the Medicare program.

Steven Brill, in “Bitter Pill,” his epic special report for TIME, demonstrated very clearly that health care prices in the United States make us outliers when compared to all other nations (2). This has resulted in by far the most expensive health care system, though we fall far short on universality, quality, equity and efficiency. In their classic report of a decade ago, “It’s the Prices, Stupid: Why the United States Is So Different from Other Countries,” Gerard Anderson, Uwe Reinhardt and their colleagues removed any doubt about our excessive prices (3).

Brill, again in “Bitter Pill,” has shown that the private insurance industry has not been effective in bringing cost escalation down to sustainable levels. On the other hand, he demonstrates quite clearly that Medicare has been much more effective in this endeavor than has the private sector.

A half century ago, Nobel laureate Kenneth Arrow, in his classic paper, “Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care,” demonstrated decisively that free markets do not work in health care (4). Except occasionally at the margin, neither patients, nor private insurers working as patients’ intermediaries, are able to obtain optimal prices for health care. Although anti-government proponents of free markets have contended that their ideological preference would save us money in health care, it has been no more than a dream on their part since they have presented no substantial evidence to refute Arrow’s conclusions.

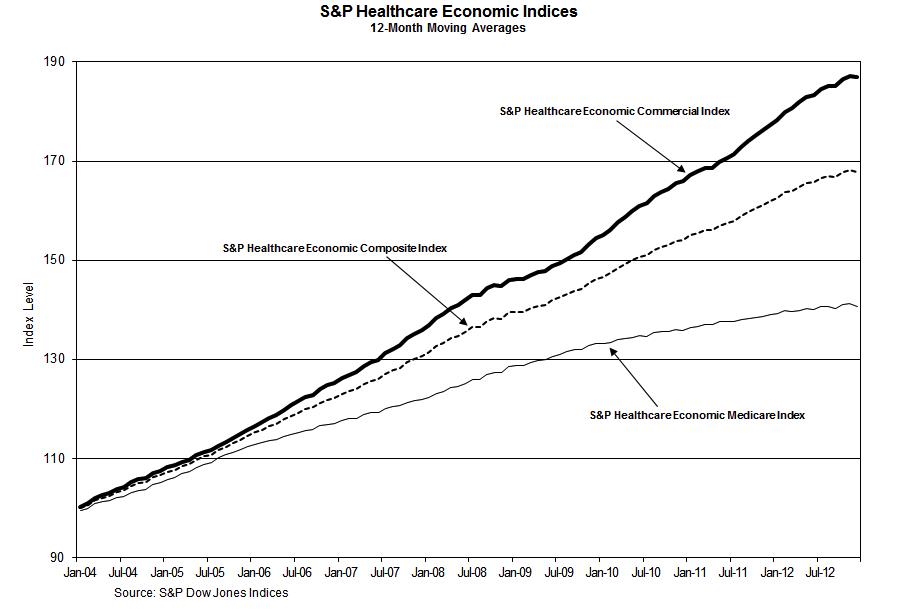

In the managed care revolution, private insurers did take one step forward in slowing the growth of costs by contracting with health care professionals and institutions, but experience has shown that the efforts of private insurers are relatively feeble when compared to the tremendous power of government administered pricing. This is demonstrated by the S&P Healthcare Economic Indices, which indicate the change in the average per capita cost of health care services (5). When breaking down the S&P Healthcare Economic Composite Index into the S&P Healthcare Economic Medicare Index and the S&P Healthcare Economic Commercial Index (private insurers and large self-funded employer groups), it is clear that Medicare has bent the cost curve when compared to the private commercial insurers (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – S&P Healthcare Economic Indices

This difference can be explained by the more rigid control that the government has over Medicare pricing. With the advice of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), an independent congressional agency, Congress sets payment rates. Through Medicare prospective payment, efforts are made to set payments based on costs rather than on prices (6). As an example, hospitals are paid based on diagnosis related groups adjusted for medical severity (DRGs), which are bundled payments based on average operating and capital costs.

Prospective payment is not always perfect, as exemplified by the difficulties with physician payment based on the flawed formula of the sustainable growth rate (SGR). Because of physician response to SGR in adjusting the frequency and intensity of services, and because of primary care/specialty distortions in the recommendations of AMA’s Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC), calculated adjustments would have caused a decline in physician payment rates that could threaten Medicare with an exodus of physicians no longer willing to participate in the program. Congress has overridden the scheduled reductions and is working on a replacement for SGR that would ensure fair payments. The response of Congress to this flaw shows that the system still works as long as the stewards remain attentive.

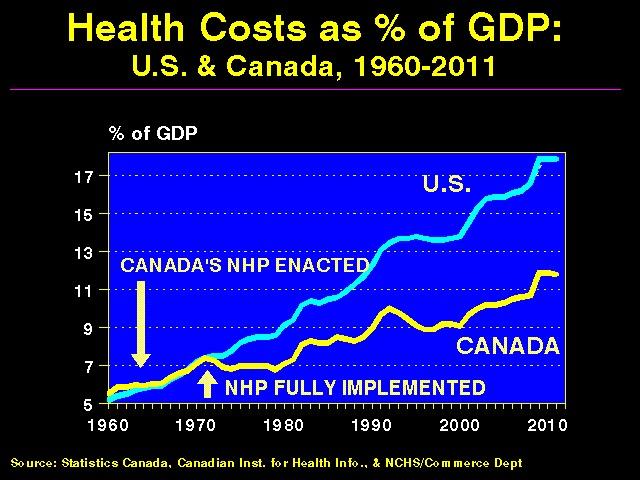

Even though Medicare has done a better job than the private sector at getting prices right, comparisons with other nations have shown that we can do even better. The United States and Canada were on the same trajectory in growth of health care costs until Canada adopted its medicare program – a single payer national health program administered in each province. Figure 2 demonstrates that, compared to the United States, Canada has effectively bent the cost curved for their entire national health expenditures.

Figure 2 – Canada bending the cost curve

This dramatic difference between the United States and Canada in the percent of GDP that is devoted to health care cannot be explained by price differences alone. Canada uses other important single payer policies to achieve their more efficient use of health care funds. One of the more important differences is that their single payer system is much more administratively efficient than our fragmented, multi-payer system. In the United States, about 30 percent of health care spending goes to administrative services, whereas in Canada, the percentage is about half that. Instituting this one change alone would bring down the trajectory of health care spending in the United States, making spending more tolerable.

As quoted in Steven Brill’s article, John Gunn, chief operating officer of Sloan-Kettering, stated, “I could see where a single payer approach would be the most logical solution. It would certainly be a lot more efficient than hospitals like ours having hundreds of people sitting around filling out dozens of different kinds of bills for dozens of insurance companies.”

Other effective policies include global budgeting of hospitals and institutions. Rather than having complex, detailed billing for each medical encou

nter, hospitals would operate on global budgets just as our police and fire departments do now. Budget negotiations are based on legitimate costs with appropriate operating margins for extra needs such as surge demand or safety net functions. System capacity is set by separate budgeting of capital improvements, ensuring that capacity is adequate for the needs, while avoiding excess capacity that can result in overutilization. Pricing for pharmaceuticals and medical supplies can be improved through negotiated bulk purchasing, just as we have with the VA system. Payment rates for physicians and other health professionals can be set through negotiations based on legitimate costs and fair net compensation.

Some express concern that, by expanding the system to cover everyone while controlling spending through a publicly administered system, there would not be enough funds to ensure a robust health care delivery system. The experiences of virtually all other wealthy nations demonstrate that this should not be a concern. Although their systems do require constant oversight by their public stewards, they have shown that they can achieve high system performance at costs that are considerably below those of our dysfunctional system here in the United States.

Physicians worry that their incomes may not be adequate. The experience in Canada can be reassuring for those concerned. After Canada adopted their medicare system, physician incomes grew more quickly than the incomes of other Canadians, and continue to be considerably greater (7). The savings in a single payer system are achieved by means other than underpaying for health care services. Also, with a single payer system, attempts by conservative governments to roll back financing to inadequate levels are met with a pushback by patients and health care professionals that restricts the damage that could be done by those with an austerity agenda.

Other advantages of a properly designed single payer system, besides cost containment, include the assurance that absolutely everyone is covered automatically, that people have choice of their health care professionals and institutions, that access to all essential services is assured through central planning of system capacity, and that more efficient allocation of our health care dollars has the added benefit of improving quality.

What other option do we have? As mentioned, the Affordable Care Act will only perpetuate uninsurance, underinsurance, and the inefficiencies and high costs of a fragmented system composed of a multitude of private insurers and public plans. The cost savings provisions in the Act are a scattershot approach that cannot begin to harness costs in such a fragmented and dysfunctional system.

We have seen with Medicare that a publicly administered program can bend the cost curve. If we improved Medicare and made it our exclusive single payer system, we would be creating our own beneficent public monopsony – a single purchaser of health care enabling the attainment of optimal value for all of us. Congressman John Conyers, along with 41 cosponsors, has introduced legislation that would accomplish this – H.R. 676, the Expanded and Improved Medicare for All Act.

Let’s keep bending the Medicare cost curve, but not just for seniors and people with disabilities. Let’s bend it for all of us.

Don McCanne, M.D., is senior health policy fellow of Physicians for a National Health Program (www.pnhp.org).

1. TIME, March 4, 2013, Editor’s Desk, “The High Cost of Care,” by Richard Stengel

2. TIME, March 4, 2013, Special Report – “Bitter Pill,” by Steven Brill, http://healthland.time.com/2013/02/20/bitter-pill-why-medical-bills-are-killing-us/

3. Health Affairs, Volume 22, Number 3, May/June 2003, “It’s The Prices, Stupid: Why The United States Is So Different From Other Countries,” by Gerard F. Anderson, Uwe E. Reinhardt, Peter S. Hussey, and Varduhi Petrosyan, https://pnhp.org/system/assets/drupal/single_payer_resources/prices_stupid.pdf

4. The American Economic Review, December 1963, “Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care,” by Kenneth Arrow, http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/82/2/PHCBP.pdf

5. S&P Dow Jones Indices, Healthcare Economic Indices, http://us.spindices.com/index-family/specialty/healthcare-cost

6. Rick Mayes and Robert Berenson, “Medicare Prospective Payment and the Shaping of U.S. Health Care,” The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

7. American Journal of Public Health, July 2011, “The Impact of Single-Payer Health Care on Physician Income in Canada, 1850–2005,” by Jacalyn Duffin