By Sarah Kliff

Vox, September 2, 2014

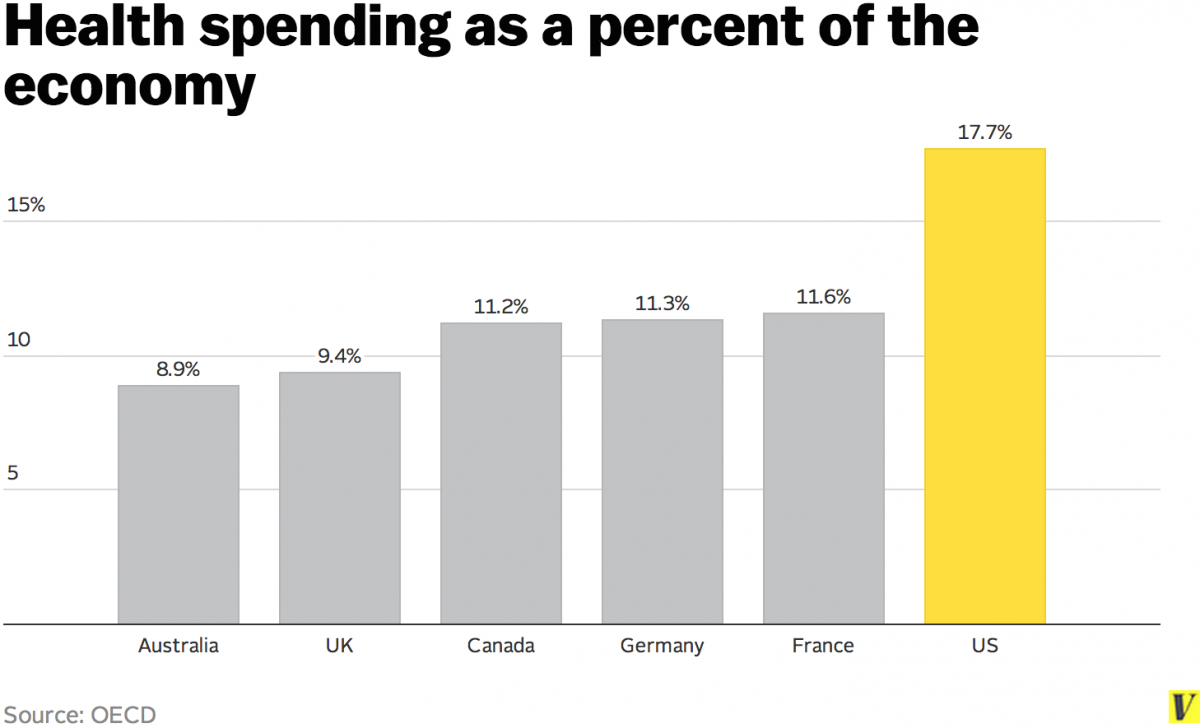

1) Americans pay way, way, way more for health care than anyone else

Health care in the United States is expensive. Insanely, outlandishly expensive.

We spend $2.8 trillion on healthcare annually. That works out to about one-sixth of the total economy and more than $8,500 per person — and way more than any other country.

If the health-care system were to break off from the United States and become its own economy, it would be the fifth-largest in the world. “It would be bigger than the United Kingdom or France and only behind the United States, China, Japan and Germany,” says David Blumenthal, executive director of the non-profit Commonwealth Fund.

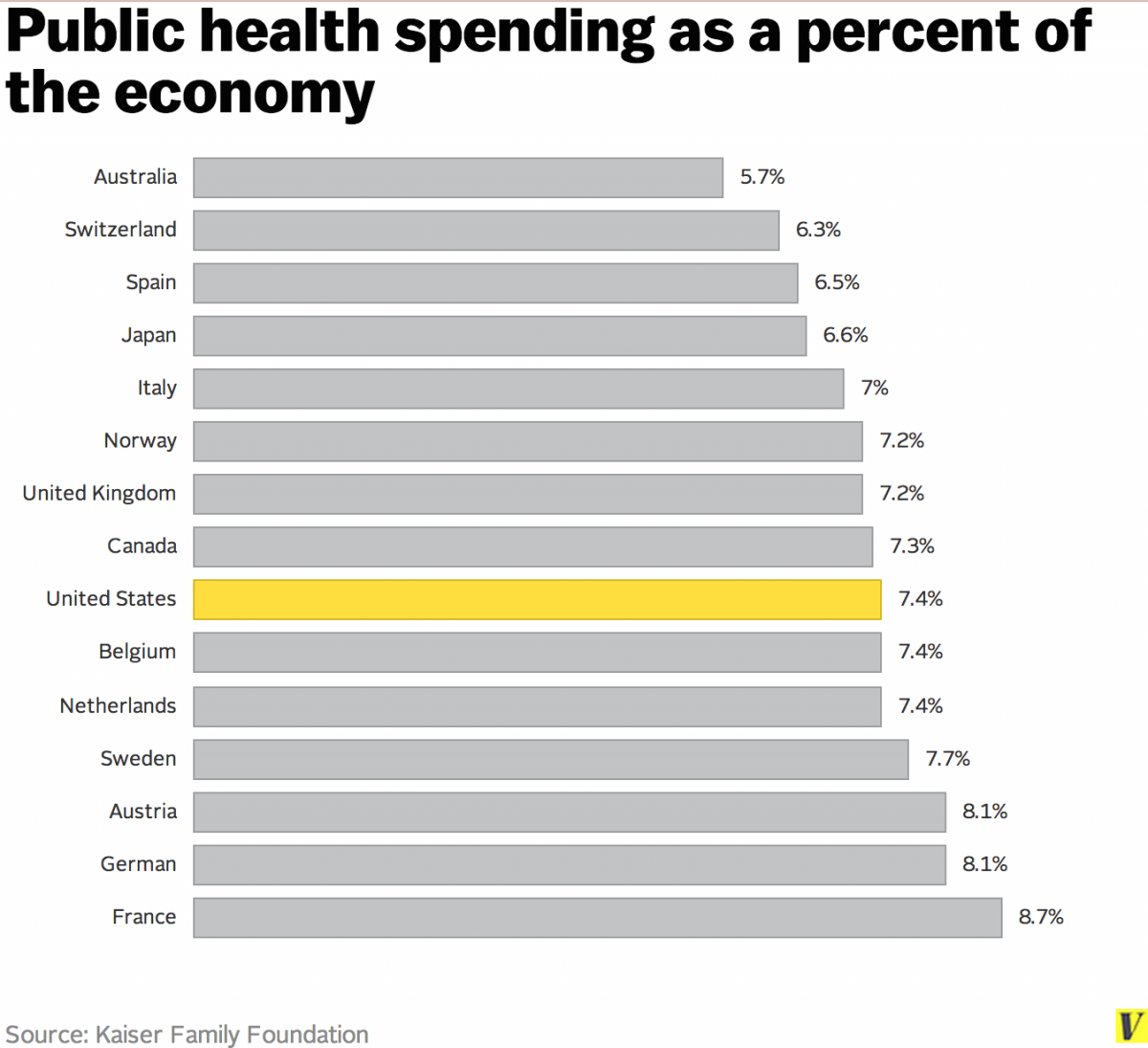

Or here’s another way to put it in its (insane) perspective: The US, which has a mostly private health-care system, manages to spend more on its public health-care system than countries where the health-care system is almost entirely public. America’s government spends more, as a percentage of the economy, on public health care than Canada, the United Kingdom, Japan or Australia. And then it spends even more than that on private health care.

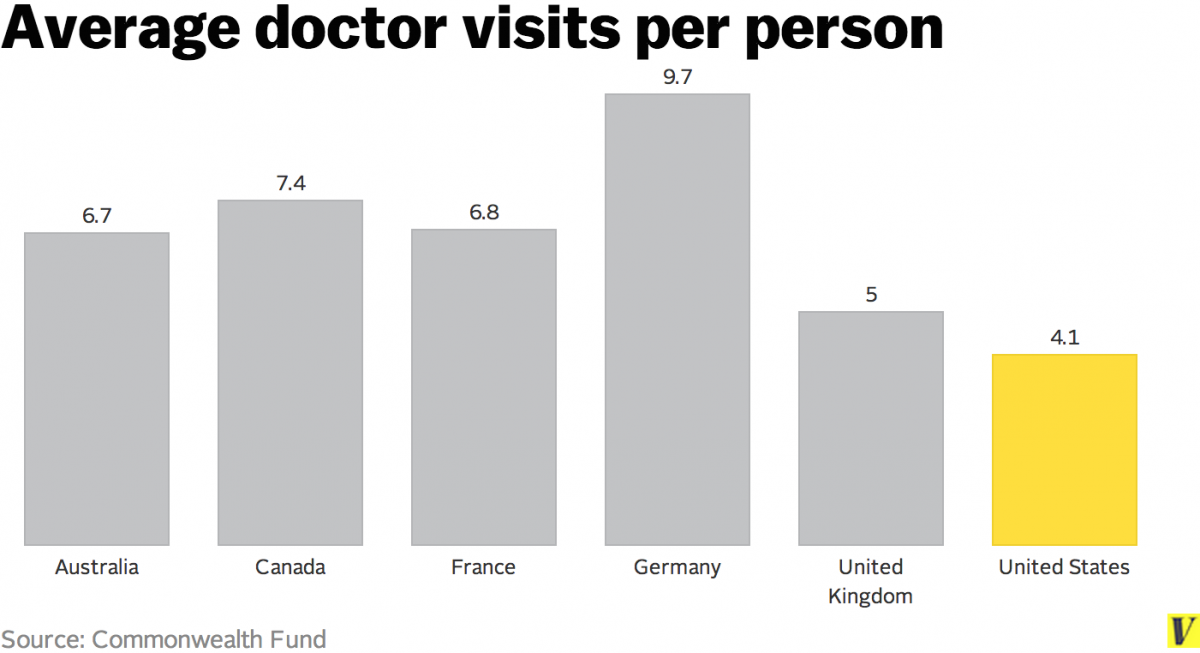

The reason that we spend so much money isn’t because we go to the doctor a ton. On average, Americans actually see the doctor less than people in other countries.

The reason that American health care is expensive is all about the price: when we go to the doctor, it costs more than when, say, someone in Canada goes to the doctor.

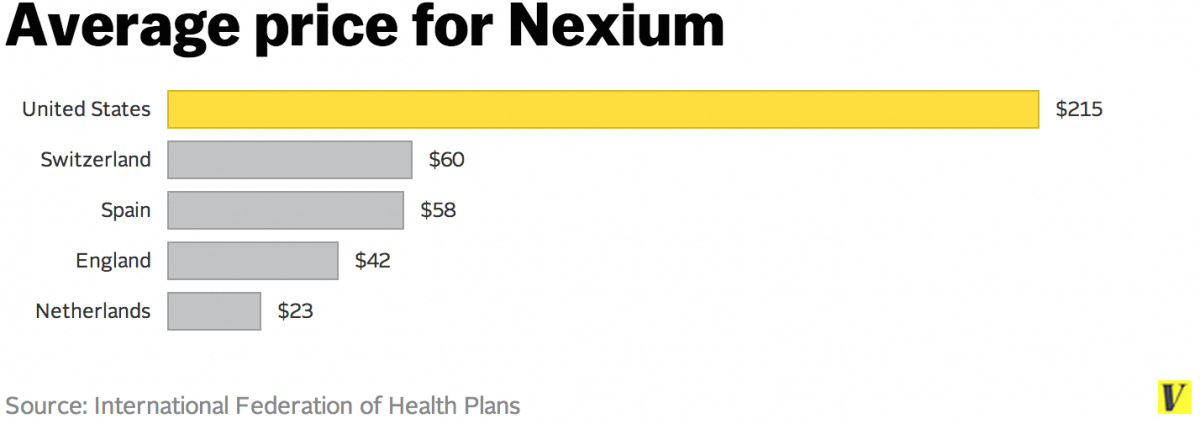

Part of this is about the price per unit of health care in the United States. From prescription drugs to imaging scans, nearly everything costs more when it’s prescribed in America. Take the heartburn medication Nexium: the exact same medication costs $215 here and $23 in the Netherlands.

Most other countries have some form of price controls; the government negotiates with drug companies and device makers for lower prices, and the government has the power to win those negotiations. The United States doesn’t do that. It leaves the negotiations up to individual insurers. And they tend to lose.

Defenders of the American system argue that price controls stifle innovation. Many say that our higher spending creates financial incentives for drug companies to come up with wonderful new drugs. And they’re probably right. But that means we’re paying higher prices to subsidize drugs for the rest of the world.

There are more nuanced ways that our health-care prices are more expensive, too. Harvard University’s David Cutler points out that we have much higher administrative costs than most other countries — and those costs get tacked onto the bill when we go to the doctor. The average American doctor spends All those extra billing specialists’ salaries have to get paid somehow — and that gets worked into our prices.

Lastly, American hospitals tend to throw more technology at health problems — a heart attack, for example, is treated with more scans and tests in America than elsewhere, and that also drives up the price of going to the doctor in the United States.

The net price of a heart attack in the United States, then, is more expensive because of the unit price of each service delivered, the more intense treatment and the additional administrative costs of processing the ultimate insurance claim.

2) We pay doctors when they provide lots of health care, not when they provide good health care

The best way for a doctor to make money in the United States right now is simple: prescribe treatments.

The American health-care system by and large runs on what experts describe as a “fee-for-service” system. For every service a doctor provides — whether that’s a primary care physician conducting an annual physical or an orthopedic surgeon replacing a knee — they typically get a lump sum of money.

That’s how most businesses work. Apple gets more money when it sells more iPads and the Ford gets more money when it sells more cars. But health care isn’t like iPads or cars. Or, at least, it’s not supposed to be.

When patients buy knee replacements, for example, what they’re buying isn’t really knee surgery itself. What they’re trying to buy is an improvement in their health.

But here’s the thing: most American doctors aren’t paid on whether they deliver that improved health. Their income largely depends on whether or not they performed the surgery, regardless of patient outcomes. Their patient’s knee could be good as new or busted as always at the end — but, in most cases, that doesn’t factor into their surgeon’s ultimate pay.

There are certainly many non-financial incentives for doctors to help their patients get better; it’s hopefully a big part of why they got into medicine in the first place. But those intrinsic motivations are often in tension with most doctors’ financial interests.

There is a growing movement in health care to change this and tether payments to patients’ outcomes. The non-profit Catalyst for Payment Reform estimates that 10.6 percent of all health care dollars paid are paid in some type of value-based arrangement, where the patient’s outcome factors into how much the health care provider earns.

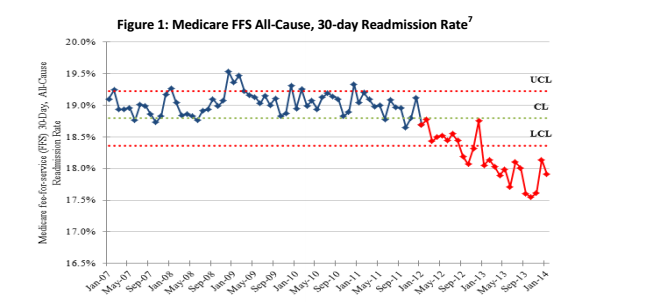

Obamacare is running dozens of little experiments in the Medicare program that also try to pay doctors more when they provide higher quality care. There are now penalties, for example, if a patient returns to the hospital after something was screwed up the first time. Those seem like they might be working; the number of preventable readmissions has steadily dropped since late 2010.

But all these experiments are on the margins of the American healthcare system. For most doctors, the bargain is as it’s always been: do more stuff, get more money.

3) Half of all healthcare spending goes towards 5 percent of the population

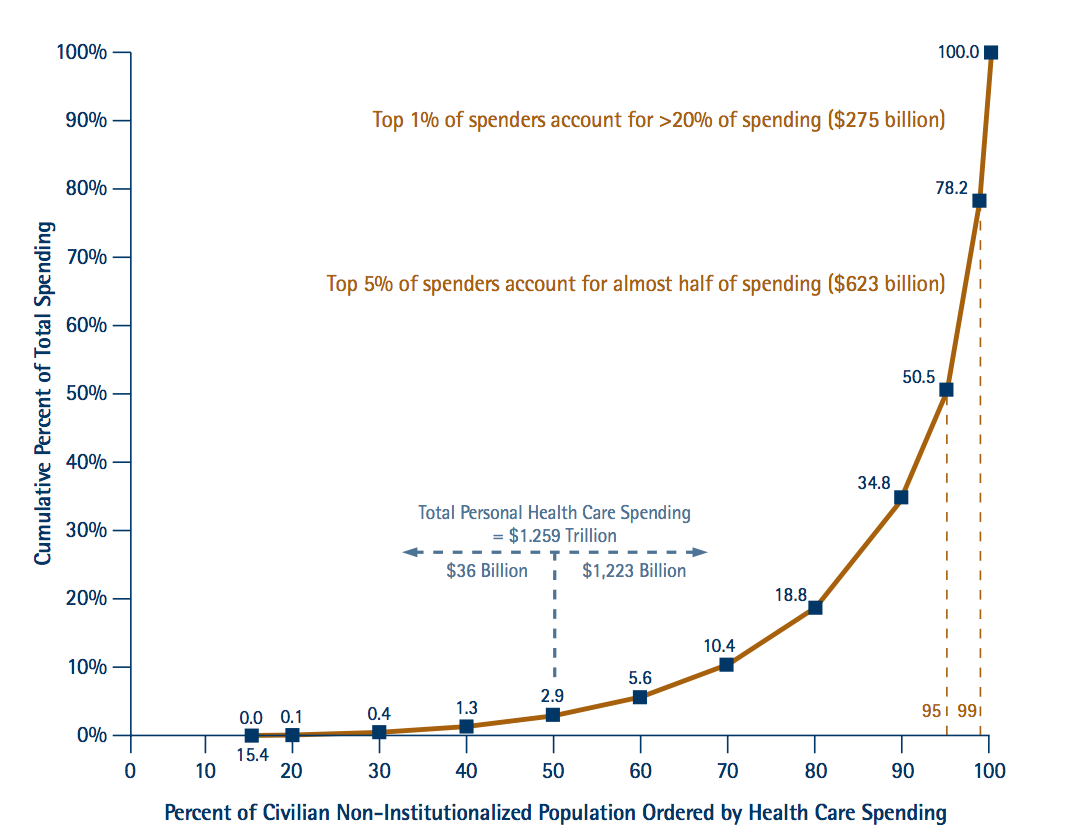

Americans are not equal health care spenders. There’s a handful of patients who use lots of medical services — and tens of millions of people who barely go to the doctor at all.

The National Institute for Health Care Management estimates that, in 2009, about half of health spending ($623 billion) went towards 5 percent of the population. On average, these are people who use $40,000 of health care annually.

The lower-spending half of the population, meanwhile, spent a paltry $236 per person during that same year.

High health-care spenders aren’t richer Americans buying up lots of health care. Instead, these tend to be the sickest patients. They are older and living with multiple chronic conditions, like diabetes and high blood pressure. These are people who take multiple trips to the hospital per year and many prescription drugs every day.

For health-care experts, this spending pattern suggests that the real space to save money is focusing on these high spenders. “What it says to me,” Commonwealth Fund’s Blumenthal says, “is we have a huge opportunity to do something that’s humane and practical by focusing extra attention these parts of the population.”

This is the approach that Atul Gawande described in his influential New Yorker article, “The Hot Spotters.” There, Gawande looked at a New Jersey practice that put extra resources towards a handful of patients who kept turning up in the emergency room. It would have nurses check up on patients to make sure they took their medications — and it worked. Patients got better, and their spending went down.

Whether that type of hands-on, labor-intensive intervention can scale up in a big way remains to be seen. But the spending patterns of the health-care system suggest that the biggest gains are to be made by focusing on the sickest patients.

4) Our health insurance system is the product of random WWII-era tax provisions

If you want to understand why we are the only developed country with an employer-based health insurance — really, the only one — then you had better get familiar with the 1954 Internal Revenue Service Tax Code.

The 1954 Internal Revenue Service Tax Code is the document in which the federal government codified into law that companies can provide health insurance benefits to workers tax-free. This affirmed a 1943 IRS Tax Court ruling that had also decreed health benefits to be non-taxable.

The early decisions were made in the context of a wartime tax code. There were overwhelming taxes meant to stop wartime profiteering and keep unions from shutting down production to extract wage gains. But when health care was protected from these taxes, it immediately became incredibly valuable to workers, and companies were able to keep it tax-free even after the war. The result is that a dollar in health benefits is worth more to a worker than a dollar in wages, because the dollar in health benefits is untaxed and the dollar in wages is taxed.

“That’s a huge discount off the price of health insurance,” says Melissa Thomasson, an economist at Miami University who has written extensively on the history of health insurance. “And it happened very quietly. I looked a few years ago to find out the name of who made the decision, and it’s been lost to history.”

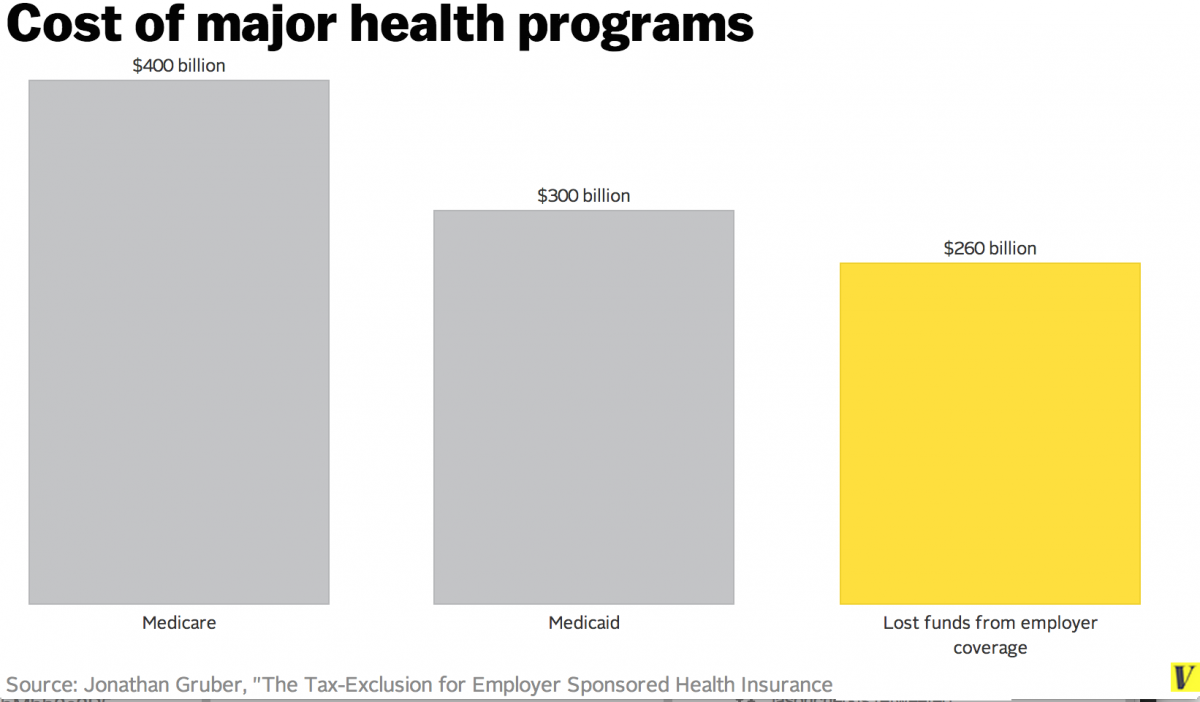

Flash forward about 80 years or so, and the health insurance tax break is the biggest in the federal budget; the government loses out on $260 billion annually by not taxing health benefits. The majority of non-elderly Americans get their health insurance at work, and with good reason: the tax-free dollar can buy a lot more medical care.

But economists on both sides of the political spectrum hate this tax break.

For one thing, it’s regressive. As a rule, people who have jobs that offer healthcare benefits are paid more than people who don’t have jobs that offer healthcare benefits — or who don’t have jobs at all. And remember that someone is ultimately paying for this tax break. In short, we’ve created a tax system where the people with good jobs are getting their health care subsidized by the people with worse jobs or even no jobs.

The tax exclusion also drives up demand for expensive health insurance. Partly, this is because of the subsidy. But partly, it’s because employees usually don’t know the real prices of their health benefits. Though ultimately economists believe that the money employers spend on health benefits comes from the money they would have spent on wages, workers don’t feel the direct cost of their health-insurance choices, and so they have little reason to try to keep spending low.

Doing away with the tax exclusion might seem like a no-brainer, but it’s very politically difficult. It would mean a huge price increase on employer-sponsored insurance, which is not a popular platform to run on (John McCain got nailed for suggesting capping, not eliminating, this particular tax exclusion).

Obamacare did manage to make some inroads. It includes a 40 percent tax on the most expensive insurance plans that starts in 2018. Know as the “Cadillac tax,” this fine will hit any insurance plans that cost more than $10,200 for an individual or $27,500 for a family. That tax is meant to push back against the too-generous plans that the tax exclusion encourages.

What the Cadillac tax does not do is eliminate the tax-exclusion for employer-sponsored coverage. Instead, it puts a dent in a 60-year-old policy — one that was set up with little forethought and is pretty much universally derided by health economists on both ends of the political spectrum.

5) Insurance companies have small profit margins

Health insurance companies are an incredibly easy target for any antipathy towards the American health care system. They’re the ones that deny claims for the care that we want, but still charge an always rising premium for their coverage.

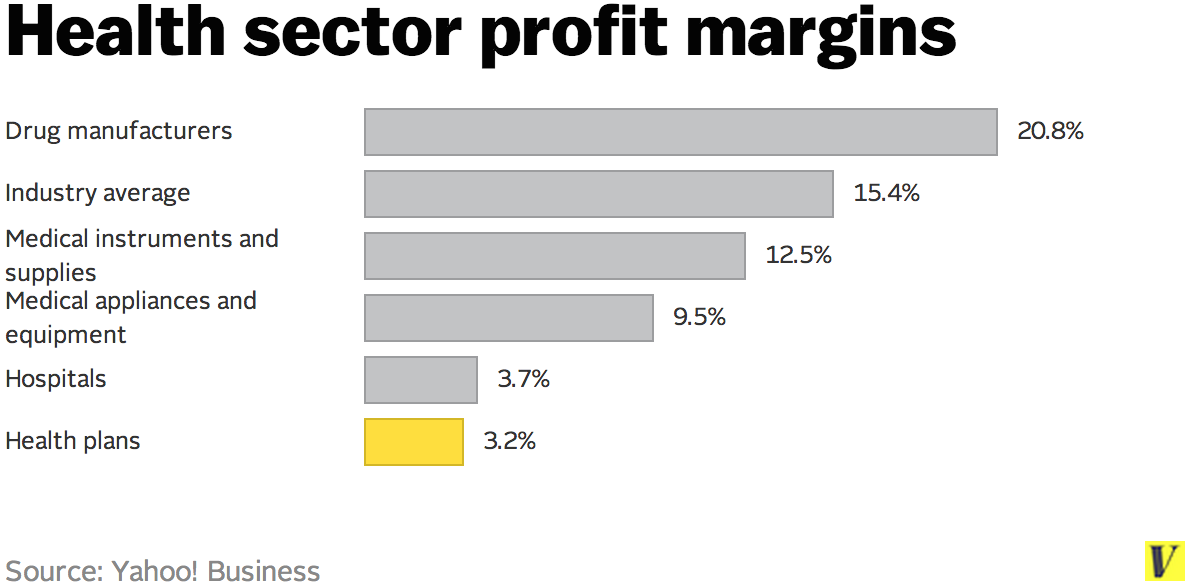

But here’s one fact about insurers that often gets lost in the debate over health care: their profit margins tend to be relatively small. Yahoo Business estimates that the health-care sector as a whole runs a 15.4 percent profit margin. Health plans, meanwhile, have an average profit margin of 3.2 percent.

“I’ve asked an audience of doctors what share of the money that goes to insurance companies gets kept there, and most audiences will guess the company keeps about 50 percent of it,” Harvard’s Cutler says. “The truth is, they keep about 10 to 15 percent of it, and most of that goes towards claims processing and administration.”

As to who makes the most money, it’s mostly drug companies and device manufacturers — the people who make the things that insurance companies buy. They typically run profit margins around 20 percent.

One reason the cost of American health care is so high is that insurers are so weak. Having hundreds of different carriers, for example, means no one insurer has lots of negotiating power — hence those high prices drug and device makers can charge.

This suggests that tamping down on insurers’ profits won’t do much to tamp down on overall healthcare costs. They’re not pocketing a large amount of premiums; instead, they’re spending those premiums on a really expensive medical products.

“Only a nickel of your premium dollar stays with the insurance company,” says Uwe Reinhardt, a health economist at Princeton University. “The profits of insurance companies are truly a trivial part of national health spending.”

Video break!

We have covered a lot of territory — and still have a little ways to go. So now’s as good of a time as any to take a short breather and be thankful for how well the airline industry works.

Or, at least grateful for the fact air travel isn’t like health care. Even with the lengthy delays, terrible food and undignified battles over reclining chairs, just imagine how much worse your flights would be if a hospital called a shots. That, as this video underscores, would be utterly horrifying.

6) Getting health care in the United States is dangerous

We don’t know exactly how many Americans are killed in hospitals each year, but we do know that it is a lot.

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine published a seminal report titled To Err is Human, which estimated that at least 44,000 patients — and as many as 98,000 — die in hospitals each year as results of medical errors.

Even using the lower-bound figure, that would mean medical errors in hospitals kill more people annually than “such feared threats as motor-vehicle wrecks, breast cancer, and AIDS.”

A follow-up study published in 2013 argued that the IOM numbers were a vast underestimate, and that medical errors contribute to the deaths of between 210,000 and 440,000 patients. At the lower bound, that’s the equivalent of nearly 10 jumbo jets crashing every week — or the entire population of Birmingham, Alabama dying every year.

“It’s a big problem,” says Commonwealth Fund’s Blumenthal. “There has not been anything like the progress we should have expected or could have had since the To Err is Human report.”

He argues that the problem with hospital errors has much to do with medical culture, in which doctors rarely discuss their mistakes. Blumenthal remembers, shortly after the landmark IOM report came out, trying to start up a consulting business that would teach hospitals how to reduce errors.

“I thought it was this great little consulting opportunity,” he says. “But there was just no interest. It was sobering, and it made clear that abstract data was not going to change the behavior of complicated health care institutions.”

And on their own, patient deaths are small events that often happen with little notice or fanfare, making them less noticeable than other events.

“Even here in Houston, if a small plane crashes by the airport, that makes the evening news,” says John T. James, founder of Patient Safety America, who authored the 2013 report. “But people dying in hospitals are happening one at a time and in insolation, and we pay less attention.”

James has argued that the United States should have something akin to the National Transportation Safety Board, which investigates every plane crash in the United States, except for patient deaths from medical errors. Even if it couldn’t get to each and every case (there are thousands more patient deaths than airplane accidents), it would create some federal oversight that, right now, does not exist.

7) One third of healthcare spending isn’t helping

The United States spends $765 billion annually (about one third of our overall health care dollars) on things that do not make Americans any healthier.

“I’m always amazed at these conversations I have with physicians,” says Amitabh Chandra, a health economist at Harvard. “They’ll openly say that about 50 percent of what happens in medicine is waste, but it’s hard to always know which care was wasteful and which wasn’t.”

Much of the waste in our system has to do with the fact that we run an inefficient health-care system, in which hundreds of health insurance plans all charge different prices for the same surgeries and scans. That requires lots of billing staff: for every three doctors in the United States, there are two administrative staff to handle all the paperwork. That’s unique to the US system.

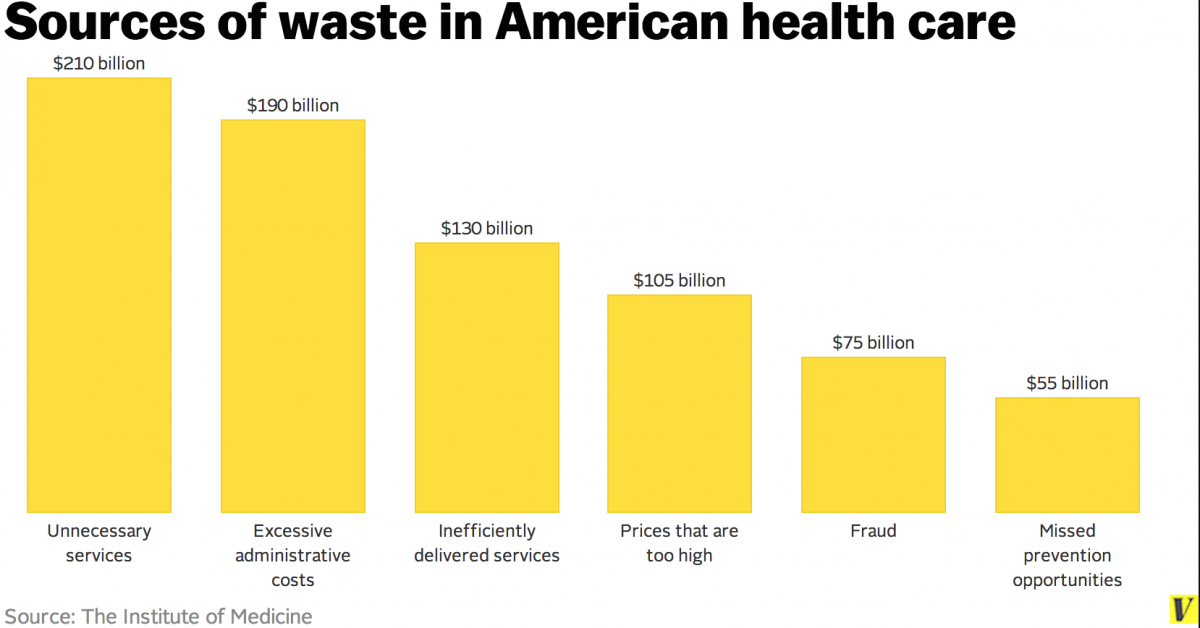

In addition, there’s unnecessary care: of the $765 billion wasted each year, the Institute of Medicine estimates that $210 billion is spent on medicine we don’t need.

Aside from being a waste of money, this extra medicine can be harmful.

Take the example of prescribing antibiotics for acute bronchitis. Researchers have known for decades this isn’t an effective treatment, but nearly three-quarters of doctors do so anyway. Those prescriptions are actively harmful, as overuse of antibiotics can speed up the creation of deadly, antibiotic-resistant superbugs. Wasteful spending doesn’t just mean extra dollars put towards health care — in cases like this, it also means worse care.

Unfortunately, most situations of waste aren’t as easy to recognize as the overprescribing of antibiotics. At many appointments, doctors have difficulty knowing when treatment is needed — and when it won’t provide help at all.

The medical community tries to address these issues with comparative effectiveness research. As the name suggests, these studies compare the effectiveness of one treatment against another for a given patient population. Many national health insurance programs use comparative effectiveness research, for example, to decide which drugs they will cover, aiming to pick the medication that gives the best results at the most affordable price.

But comparative-effectiveness research doesn’t always offer clear directions. Study methods can be faulty and results contradictory; one drug might work great for certain patients but terribly for others. These studies can also be controversial and met with outcry over rationing.

When the government, for example, recommended lowering the frequency of breast cancer screenings — more screenings, decades of research had found, didn’t save any more lives — there was public outcry.

And that’s one of the really tough issues with cutting down on waste in medicine: there are lots of healthcare treatments that we want, even when it might not actually be health-care treatment that we need.

8) Obamacare is not universal health care

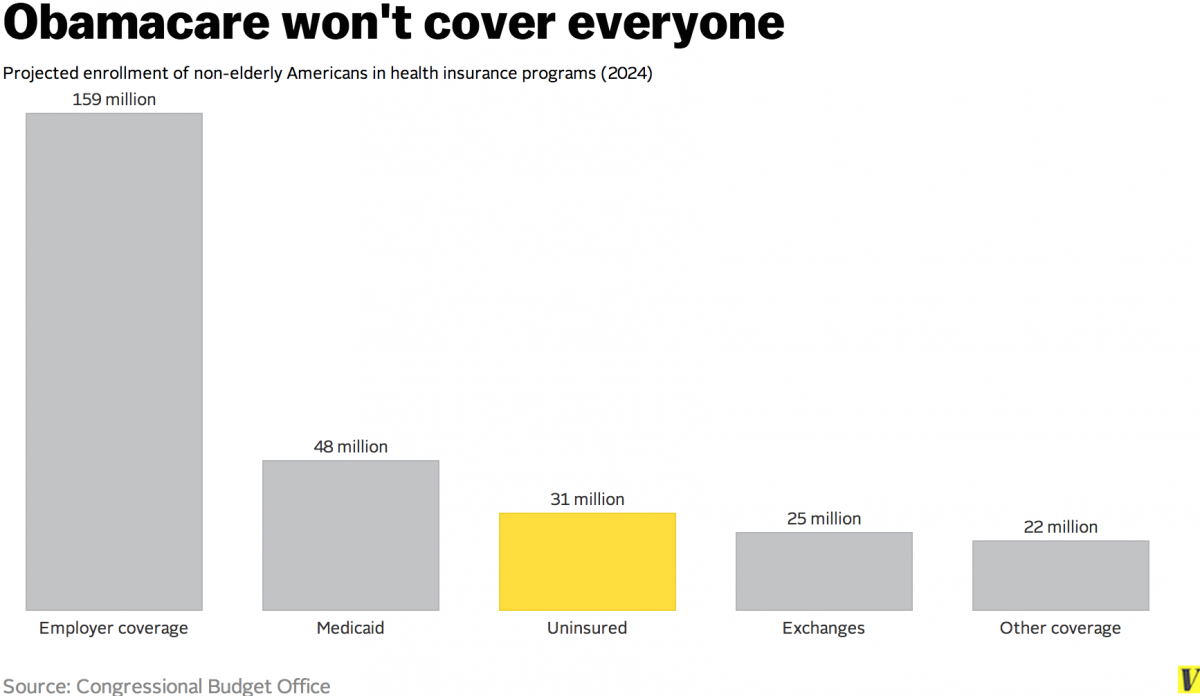

The United States does have a very recent, very large expansion of health insurance coverage — that’s the program we all call Obamacare. It’s expected to cover an additional 26 million people by 2024.

What the United States does not have, however, is universal coverage.

Obamacare doesn’t eliminate uninsurance in America; instead, it cuts the number of people lacking coverage about in half. Even after Obamacare is fully implemented, budget forecasters still expect that 31 million Americans will lack insurance coverage — a bigger group than the people buying coverage on the exchanges. Our uninsured rate will still be in the double digits, hovering around 11 percent.

This group includes people who are locked out of the insurance expansion and those who do have access but decide not to participate.

Among the groups left out of the healthcare law are undocumented workers, who are not eligible to purchase any healthcare plans from the new insurance exchanges, and people who live in states that are not expanding Medicaid. For a sense of how big a population that is, the 10 largest states not expanding Medicaid are leaving out an estimated 3.6 million low-income residents.

There will also be millions of people who do have access to health insurance, maybe at work or through the new exchanges, but decide not to enroll. Maybe they think its too expensive — lots of shoppers felt that way during Healthcare.gov’s open enrollment — or maybe they don’t think health insurance will help them. Many of these people will face a penalty for not purchasing insurance coverage.

This will continue to set the United States apart from most other industrialized nations, in which universal coverage is the standard. And it means there will still, in decades to come, be people who can’t afford health insurance. That means there will be millions who rely on free clinics for medical care.

http://www.vox.com/2014/9/2/6089693/health-care-facts-whats-wrong-american-insurance