PNHP’s 2018 Annual Meeting in San Diego drew physicians, health professionals, and advocates from across the country. To access a selection of slideshows and handouts from the meeting, please see below. To view photos and video from the meeting, visit our Flickr and YouTube pages.

We also encouraged PNHP members and supporters to post to social media using the hashtag #PNHP2018. Click here to read member tweets, and be sure to view our one-page social media guide so you can continue sharing single-payer content in the future.

Leadership Training (Nov. 9)

Agenda & schedule for the Leadership Training

Speaking for Single Payer

By Ed Weisbart, M.D. and Claudia Fegan, M.D.

Download slideshow here

Answering Difficult Questions

By David Himmelstein, M.D. and Steffie Woolhandler, M.D., M.P.H.

Activist Techniques 101: Lobbying and Bird Dogging

By Carol Paris, M.D. and Darshali Vyas

Download handout here

Deep Listening & Storytelling: Tools for Effective Leadership

By Frances Gill and Augie Lindmark

Working with Media

Natalie Shure, M.A. and Clare Fauke, B.A.

Download slideshow here

Download handout here

Building a Successful Chapter–and Having Fun Along the Way

By Jessica Schorr Saxe, M.D., Denise Finck-Rothman, M.D. and Kay Tillow

Download slideshows here and here

Download handouts here, here, here, and here

Communicating with Conservatives

By George Bohmfalk, M.D.

Download slideshow here

Download handout here

Civic Power through Engagement

By Matt Moy, M.D., Kina Collins, and Kaytlin Gilbert

Download slideshow here

Rally to Tear Down Barriers to Care (Nov. 9)

Leadership Training participants marched from the Pendry Hotel to the nearby Immigration and Customs Enforcement (I.C.E.) office where we demanded an efficient, effective, and humane health care system that covers all residents of the United States, regardless of immigration status.

PNHP members rallied with several local organizations, including Women’s March San Diego, San Diego Border Dreamers, and Border Angels.

Our members created signs in the morning, prior to the march. Click here for advice on how to make your own protest sign and email organizer@pnhp.org for advice on how to organize a single-payer rally in your community.

Annual Meeting (Nov. 10)

Agenda & schedule for the Annual Meeting

Download workshop descriptions and speaker bios

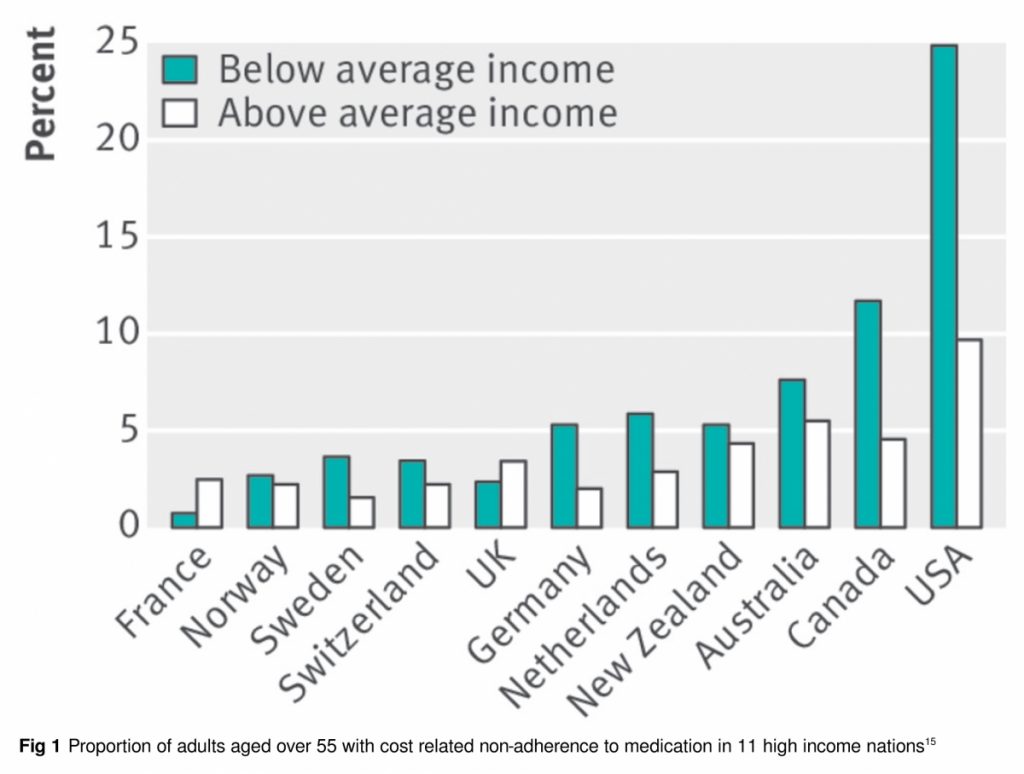

Health Policy Update

By David Himmelstein, M.D. and Steffie Woolhandler, M.D., M.P.H.

Download long slide set here

Download short slide set here

Download alternate visual from Dr. Ed Weisbart here (long version)

Download alternate visual from Dr. Ed Weisbart here (short version)

Barriers to Care

Panel moderated by Claudia Fegan, M.D. and featuring Altaf Saadi, M.D., M.S.H.P.M. (Immigration); Charlene Harrington, Ph.D., R.N. (Long-Term Care); and Scott Goldberg, M.D. (Physician Burnout)

The Mass Incarceration of People with Serious Mental Illness in the United States Since the 1980s

By Philippe Bourgois, Ph.D., Professor of Anthropology and Director of the Center for Social Medicine and Humanities, UCLA

Reproductive Health: The Third Rail of Health Care

By Panna Lossy, M.D. and Norma Jo Waxman, M.D.

Download slideshow here

Policy Pitfalls: Faux Single-Payer Plans and Legislative Deficiencies

By David Himmelstein, M.D. and Adam Gaffney, M.D.

Download slideshow here

Long-Term Care Coverage

By Charlene Harrington, Ph.D., R.N. and Jedd Hampton, M.P.A.

Download slideshow here

Download handout here

Physician Burnout

By Scott Goldberg, M.D.; Anna Darby, M.D., M.P.H.; Leo Eisenstein; and Gordon Schiff, M.D.

Download slideshow here

Download handouts here, here, and here

Treating Overtreatment

By Michael Hochman, M.D., M.P.H.

Download slideshow here

Immigrant Health

By Altaf Saadi, M.D., M.S.H.P.M. and Nicte Mejia, M.D., M.P.H.

Building a Feminist, Multi-Racial, Pro-Immigrant Movement for Single Payer: Why and How?

By Roona Ray, M.D., M.P.H.

Download slideshow here

What Went Wrong with Health Care? Commercialization, Managerialism, and Corruption

By Roy Poses, M.D. and Wally Smith, M.D.

Download slideshow here

Lessons from California for State-Based Single Payer

By Paul Song, M.D.; Bonnie Castillo, R.N.; and Micah Johnson, M3

Download slideshow here

Download handout here

Medicare-for-all in the House and Senate

By Alex Lawson and Eagan Kemp

Attacks on the V.A.

By Suzanne Gordon

Download slideshow here

Download handout here

Allies for Single Payer

Panel moderated by Carol Paris, M.D. (PNHP) and featuring Bonnie Castillo, R.N. (National Nurses United); Wendell Potter (Tarbell.org); Dylan Dusseault (Business Initiative for Health Policy); and Augie Lindmark (Students for a National Health Program – SNaHP)

Dinner Speaker

Linda Rae Murray, M.D., M.P.H., Past President, American Public Health Association

CME Credit

Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP) was pleased to partner with the American Public Health Association (APHA) to offer Continuing Medical Education (CME) credit for physicians and qualifying medical professionals who attended our 2018 Annual Meeting. Participants were eligible for a maximum of 6.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits.

Click here for instructions on claiming your CME credit after the meeting.